Throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s, there were few hospitals in Japan quite like Hiroshima’s Shima Hospital.

First opened in August 1933 by the anti-war, United States-educated Dr. Kaoru Shima, the two-story brick hospital had around 50 patient rooms, an extensive surgery unit, and was equipped with the most advanced medical technology of the time.

Modeled after Minnesota’s famed Mayo Clinic, the Shima Hospital was an affordable multi-speciality practice, rare in a country whose hospitals followed a more traditional, European style of applied medicine.

Dr. Sasaki lost all sense of profession and stopped working as a skillful surgeon and a sympathetic man; he became an automaton, mechanically wiping, daubing, winding, wiping, daubing, winding.

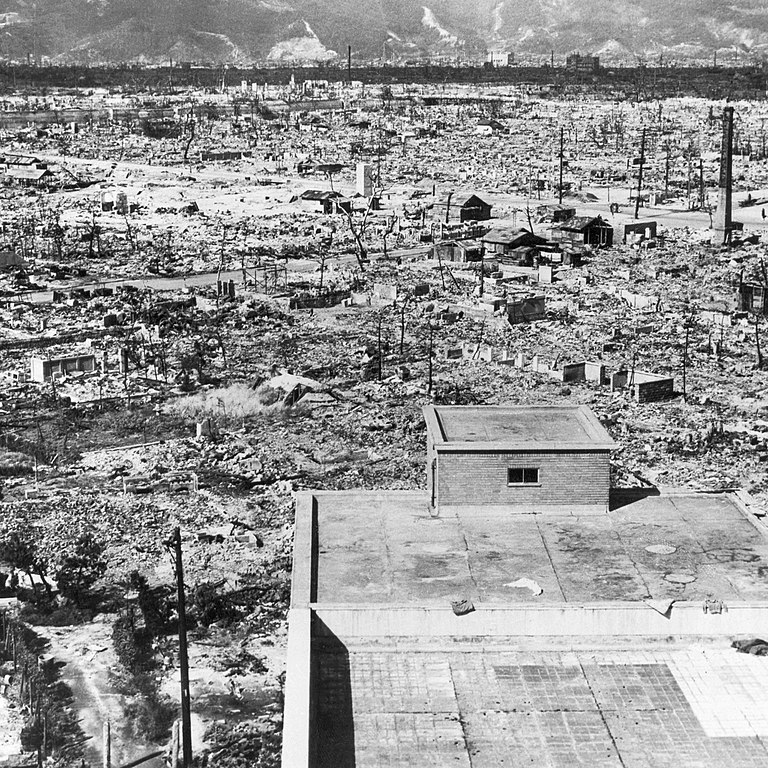

On August 6, 1945, there were around 50 patients, and around 30 staff, at Shima Hospital when the Enola Gay dropped the world’s first atomic weapon, the 15-kiloton ‘Little Boy’, on Hiroshima.

Though the bomb was aimed at an iconic nearby bridge, the clinic would serve as the resulting atomic explosion’s hypocenter, 1900 feet beneath the denotation point.

Along with up to 146,000 human lives, and mankind’s pre-nuclear innocence, the hospital vanished, 75 years ago this Thursday.

“The stench of the dead is nauseating … the only parts of Hiroshima apparently not destroyed by the atomic bomb are the graveyards,” Lt. William B. Walsh, a U.S. Navy doctor who was the first American physician to visit Hiroshima, two months after the bombing, later wrote.

“The people in this city, that is those that are left, are unfriendly and almost hostile. They had that look in their eyes that asks you resentfully, ‘why did you do this to me?”

Medical services decimated

Those surviving Hiroshima residents who met Walsh had suffered much, with virtually no medical professionals to help them.

Of the 300 doctors in Hiroshima at the time of the explosion, the Red Cross says 270 (90 percent) were killed or injured. Of the 1780 nurses, 1654 (93 percent) suffered the same fate.

Dozens of hospitals were destroyed, while remaining facilities were often so badly damaged, and under-staffed, that even basic treatment was impossible.

Initially, Hiroshima’s Red Cross Hospital was the only hospital functioning, with just one uninjured physician, Terufumi Sasaki, able to help the tidal wave of blast victims.

“Before long, patients lay and crouched on the floors of the wards and the laboratories and all the other rooms, and in the corridors and on the stairs and in the front hall,” John Hersey, an American journalist, later wrote of Sasaki’s experience for the New Yorker.

“Wounded people supported maimed people; disfigured families leaned together. Many people were vomiting. A tremendous number of school girls – some of whom had been taken from their classrooms to work outdoors, clearing fire lanes – crept into the hospital.

“Tugged here and there in his stockinged feet, bewildered by the numbers, staggered by so much raw flesh, Dr. Sasaki lost all sense of profession and stopped working as a skillful surgeon and a sympathetic man; he became an automaton, mechanically wiping, daubing, winding, wiping, daubing, winding.”

As ferocious fires swept the city, the Army-Marine Headquarters—known as the ‘Akatsuki Corps’—took the lead on recovery efforts in the first few days. Though having to deal with a profound shortage of basic medical supplies, volunteer medical staff from Kure and Hatsukaichi quickly headed to Hiroshima to help.

“The rescue effort suffered from a drastic shortage of medicines, bandages, and other medical supplies,” the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum wrote. “Thousands died who might have been saved by adequate first aid.”

Acute radiation syndrome

Most patients were either covered in massive burns, suffering radiation illnesses, or both.

Though Sasaki closely monitored rapidly decreasing white blood cell counts in the initial weeks, doctors had little idea that the disturbing range of radiation symptoms were the first signs of widespread acute radiation syndrome.

“First,” Dr. Shuntaro Hida, a Japanese military doctor who worked in Hiroshima after the bombing, told VICE in 2008, “the victims get a high fever of over 104 degrees Fahrenheit. It was so high that I thought the thermometers were broken.

“Also, when you tried to get close to their faces, you noticed that they had unbelievably bad breath. It was almost impossible to go near them. I guess in medical terms you would describe the smell as a combination of necrosis and decomposition.

“When you peered into their mouths, they were completely black. Because the white blood cells in their bodies were completely dead, the bacteria in their mouths had multiplied profusely.

“And since there was nothing to protect the inside of the mouths anymore, they started to rot very quickly without even going through the usual stages of inflammation or pus formation.

“This rot was what we were smelling. It’s a smell that only the medics who experienced the aftermath know about.”

Hida noticed blotchy purple petechiae starting to appear on victims’ skin, recognizing it as a condition that usually occurred soon before a blood disease sufferer dies.

“After that, their hairs would all fall out, as if their heads had been swept with a broom,” Hida told VICE.

“Radiation usually targets healthy cells, so hair roots are the first to go. The final symptoms are vomiting blood, as well as hemorrhaging from the eyes, nose, anus, and reproductive organs.

“The victims only last a few hours after this before they die. At the time, we were all extremely scared, because obviously nobody knew what was causing all this.”

“The petechiae in particular became an obsession, a mark of death to those affected,” Australian Doctor noted, in an impressive 2015 feature on the medical aftermath of the bombing.

The ‘hibakusha’

More than 10,000 people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which had a second atomic bomb dropped on it on August 9, 1945, died of acute radiation syndrome, initially. Midori Naka, a famed Japanese actress, was its first recognized case following the atomic bombings.

It is understood that around 400,000 survived, later to be known as the hibakusha, or ‘bomb-affected people.’ Covered by keloid scars and rubbery lesions, the hibakusha were deeply shunned in Japanese society before being offered free lifetime healthcare in 1957.

Several hundred are still alive in the United States. Though attracting criticism for not treating the victims, the U.S. Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission’s research on the hibakusha would become one of the longest epidemiological medical studies ever.

…the physical effects of atomic bombs will probably end with the death of the hibakusha generation.

While Sasaki’s work helped form the foundations of knowledge on acute radiation syndrome, further research would show the increased rates of post-attack leukemia from those exposed to the blast, as well as an 11 percent higher chance of other cancers.

Despite initial fears, studies, both at the time and decades later, showed that radiation doses by Hiroshima parents were no more likely to lead to birth defects, or future health problems, for children, than those not exposed.

“It suggested the physical effects of atomic bombs will probably end with the death of the hibakusha generation,” Australian Doctor continued.

Thanks to the hard work of the doctors who treated them initially means what happened to them, and those that were killed on August 6, 1945, will never be forgotten.

Nor will the spirit of Shima Hospital.

Shima—who, along with a nurse, survived the atomic attack as he was assisting a difficult surgery in a nearby town—would rebuild his clinic in 1948.

Though he died in 1977, ‘Shima geka naika’ is still operating today, headed by his grandson, Hideyuki.