Amongst the enduring images taken during the Covid-19 global pandemic, few may ultimately match the simple, heartbreaking power of those shared from India over recent weeks.

Car parks and small patches of urban land covered in funeral pyres, often fueled by wood cut down from nearby city parks. Smoke billows after they are lit, while groups of men in masks and white personal protective equipment look on.

Raw and uncomplicated, they feel like moments from a pandemic long-past; scenes of an old world finding itself again, in the new.

“If we get more bodies, then we will cremate on the road,” Jitender Singh Shanty, who is organizing more than 100 daily cremations in Delhi, told the Guardian. “There is no more space here … we had never thought that we would see such horrible scenes.”

Despite more than 3.3 million now dead from Covid-19 worldwide, the sheer human scale of what is happening in India is hard to comprehend, let alone process.

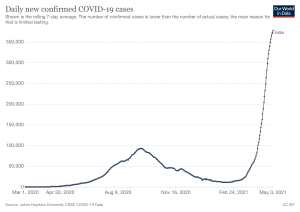

On Saturday, it announced 401,993 new positive cases; a new daily world record. Yesterday—a ‘reassuring sign’—357,488 were recorded.

Both figures are larger than the entire pandemic’s total infection numbers in nations like Greece or Croatia, and more than three times larger than China’s official total.

More than 20.3 million Indians have tested positive, while its death toll stands at over 222,000. More than quarter of both numbers have come in the last two months. The World Health Organization say India accounted for 46 percent of all Covid cases in the past week, as well as a quarter of all pandemic deaths.

With vaccines, testing, and hospital care limited, most experts agree that India’s actual numbers may be up to ten times worse than it officially records, in what has been called a “dystopian Covid-19 wave.”

The conditions and causes for an outbreak in such a massive country seem clearly linked. A seemingly effective national lockdown last year saw a general loosening of mask and social distancing standards, and astonishingly low case numbers after a September peak.

Normal life looked set to resume. As 2021 begun, millions attended political rallies and religious festivals. At the same time a high contiguous ‘double mutant’ variant—first discovered in India late last year—were quickly spreading. Several dangerous international strains were, too.

Younger patients have been turning up to hospitals which can barely offer beds. Across Delhi, many hospitals are short on oxygen, and oxygen cylinders. Medical school exams have been postponed, enabling a generation of trainee doctors to join over-stretched frontline medical professionals in confronting the crisis. For those dealing with the situation on the ground, the mental toll is considerable.

What we had been fearing during last year’s first wave, and which never really materialized, is now happening in front of our eyes: a breakdown, a collapse, a realization that so many people will die.

A nationwide vaccine rollout—set to be one of the biggest in human history—seems largely stuck in first gear. The black market for oxygen cylinders is thriving. Funeral pyres keep covering car parks, and unused land.

“Then, it was the fear of the unknown,” Jeffrey Gettleman, the New York Times South Asia bureau chief, recently wrote, describing the difference from India’s ‘first wave’ last September.

“Now we know. We know the totality of the disease, the scale, the speed. We know the terrifying force of this second wave, hitting everyone at the same time.

“What we had been fearing during last year’s first wave, and which never really materialized, is now happening in front of our eyes: a breakdown, a collapse, a realization that so many people will die.”

For the massive Indian medical community across the world—including around 15,000 medical students and residents with Indian heritage in the United States alone—the same realization has never made home feel so far away.

“It’s the million-dollar question”

On January 30, a 20-year-old Kerala woman who had recently traveled back from Wuhan, China became the first Indian to test positive for Covid-19. According to AFP, a 76-year-old man from Karnataka was the first to die from it, on March 12.

Within a month, the Indian government instituted a nationwide lockdown. With its initial phase lasting until early June, the Indian lockdown was considered one of the strictest in the world.

Announced only four hours before it began, it caused mass chaos amongst India’s vast migrant worker populations. Up to 100 million people were stranded without income, hundreds of miles from home. An estimated 75 million would be pushed into poverty.

Though regional lockdowns would often come into place to deal with state outbreaks, further phases of ‘reopening’ saw life continue as normal, albeit with masks. India mandated the use of masks in public spaces. Those caught without them faced small fines.

The ‘first wave’ peaked on September 1, 2020, with 93,617 recorded cases. By February, the seven-day average for cases was around 11,000, while the seven-day average for deaths was around 100. Both numbers were less than California’s, at the same time.

Led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the Indian government was hailed for its response, with mask mandates and widespread public compliance crucial in its success. For a population the size of India’s, figuring out how it all confounded medical experts around the world.

As the world’s largest producer of vaccines, India started producing millions of doses of AstraZeneca and domestically-researched Covaxin. Starting last December, 64 million doses of AstraZeneca vaccines have been shipped from India to 86 different countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, and Brazil.

“It’s the million-dollar question,” Genevie Fernandes, a public health researcher at the University of Edinburgh, told NPR in February. “Obviously, the classic public health measures are working: Testing has increased, people are going to hospitals earlier and deaths have dropped.

“But it’s really still a mystery. It’s very easy to get complacent, especially because many parts of the world are going through second and third waves. We need to be on our guard.”

It’s very easy to get complacent, especially because many parts of the world are going through second and third waves. We need to be on our guard.

Things were changing, though. By late 2020, low infection numbers led to an understandable drop in mask usage. In the meantime, India moved its Covid-19 testing more rapid, but less reliable kits, away from the ‘gold standard’ PCR test.

Modi soon declared victory over Covid-19. Having seemingly navigated past the public health crises faced in the U.S, Brazil, and the U.K, he told a World Economic Forum virtual summit on January 28 that India had saved “humanity from a big disaster by containing the coronavirus effectively.”

‘The end game’

The ‘double mutant’ (B.1.617) variant was first detected in India last October. The ‘double mutant’ variant actually has 13 variations to it, but gets its name due to two mutations similar to the other contagious international strains.

It slowly began to spread, around the same time international strains also did. The U.K (B.1.1.7) and Brazil (P1) strains have both been detected in India, with B.1.1.7 thought to be responsible for driving the upswing in positive cases in Delhi, in April.

All three are far more contagious than the initial Covid-19 strain, while the ‘double mutant’ has also spread to 21 other countries, including the U.S., Germany, Turkey, Australia, and the U.K.

Despite the spread, and the horror of expat Indians who’d experienced the winter surge in the U.S., political rallies and religious festivals proceeded. Millions participated in the Kumbh Mela festival in Haridwar as recently as mid-April.

“India’s high population and density is a perfect incubator for this virus to experiment with mutations,” Ravi Gupta, a professor of clinical microbiology at the University of Cambridge, told the BBC.

Confident in the planning of its vaccine rollout and still basking in the public success of last year’s lockdown, the Indian government was slow to respond to rising early numbers in early March. Public health officials raising alarm were largely ignored.

“Rather than making urgent preparation for a second wave of cases in an already weak healthcare system, the government put much of its focus on vaccinations — a campaign too limited to blunt the oncoming disaster,” the Washington Post reported, on April 29.

“The government repeatedly chose self-congratulations over caution, publicly stating the pandemic was in its ‘end game’ in India as recently as last month.”

By late March, the worsening outbreak finally saw the government place a temporary hold on all exports of the AstraZeneca vaccine to meet the increasing domestic need. Overall production struggled to match it, with the expansion of availability to those 18 and older being met with a lack of supply in a number of states. Manufacturers say vaccine shortages may last for months.

Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine recently gained state approval for emergency use, joining the domestic-researched Covasin and Covishield, AstraZeneca in India. Research shows most major vaccines, including Pfizer and Moderna, should still be effective against the Indian variant – though some less effectively.

More than 156 million doses have been given, covering 9.3 percent of the overall Indian population. 2.1 percent are now fully vaccinated, comparable—relative to population—to Argentina. The U.S now has 32 percent of its population fully vaccinated.

India’s high population and density is a perfect incubator for this virus to experiment with mutations.

The ‘second wave’ has forced a number of Indian states into regional lockdowns, though the government has held off another nationwide effort due to concern around its economic impact. Some say too much damage has already been done, especially amongst the hundreds of millions of migrant workers.

“This year’s exodus has resulted in a different kind of chaos: there are no quarantine centres for them to stay in before they enter their village homes,” Arundhati Roy recently wrote, in the Guardian. “There’s not even the meagre pretence of trying to protect the countryside from the city virus.”

Maharashtra, Kerala, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu are amongst those worst hit Indian states. In some towns, almost every hospital bed is filled with a Covid-19 patient.

The role of the med student

Given the urgency of the Covid-19 crisis, the extent to which India’s med students have been pulled in is not surprising.

On Monday, the government postponed the annual National Eligibility cum Entrance Test for Post Graduate (NEET-PG) courses for four more months, allowing senior med students and hospital interns to join pandemic’s frontline service early. The National Medical Commission has also told medical colleges to keep postgrad students in residencies, to provide continued support. Second and third year students are also being recruited to help.

“Medical personnel completing [one] hundred days of Covid-duty will be given priority in the forthcoming regular government recruitment programs,” the Prime Minister’s Office said.

“While medical interns shall be deployed in Covid management duties under the supervision of their faculty, final-year [medical] students can be utilized for tele-consultation and monitoring of mild Covid cases under supervision of senior faculty.”

The moves have not been universally popular with students, with some saying exam delays could impact higher study and specialization.

“We’ve been working non-stop for several months now and the government needs to understand that if they conduct exams on time, they will still have more students [and] manpower to join the Covid task force,” Anukriti Thakur, a final year resident, told the Hindustan Times.

For those Indian med students who are joining the Covid-19 response, OnlineMedEd has available a 48-lesson, 12.5-hour Crash Course in Medicine to help them quickly prepare for situations they will soon find themselves in. All types of specific healthcare individuals are covered in a simple, solid, and easily digestible program.

Like most medical education programs across the world, e-learning has defined the med school experience in India over the last twelve months. The pandemic-forced switch came just a year after the implementation of India’s competency-based medical education system, which was introduced alongside licensure reforms.

The CBME systems underscores the need for more personal supervision, mentorship, and day-to-day assessment of students, shifting the role of faculty to “guide by the side rather than sage on the stage.” Despite its benefits, remote learning can complicate its practicality.

“The Indian medical education system is currently facing many threats,” the authors of a recent study into Indian medical education concluded.

“Institutions, educators, and students can save the system from collapsing by incorporating CMBE ideals into the e-learning system. The need for a properly working health care system is vital, especially after the pandemic.

“The graduation of highly competent Indian health care professionals is achievable if all concerned parties start cooperating. Despite all the hiccups, online medical education is gaining momentum in India due to the advantages of online education and the push by stakeholders to sustain it through the pandemic.”

‘This wave of the pandemic’

Today, India brought up two straight weeks of more than 300,000 new cases a day. Despite a terrifying winter, the United States cleared that figure only once, on January 8.

Though Indian government scientific advisors say the current wave may peak this week, and official case numbers have dropped since the weekend, India will remain in the grips of the ‘second wave’ for some time yet. Early government aims to vaccinate 250 million people by July seem unlikely.

While several nations have stopped all flights from India, marooning many of their own citizens. Though the U.S. could soon do the same, it is providing assistance, sending 60 million doses of AstraZeneca, along with oxygen cylinders, rapid diagnostic tests, and 100,000 N95. The U.K, Russia and France have also sent medical supplies.

In this wave of the pandemic, it’s the young who are falling, who are filling the intensive care units. When young people die, the older among us loose a little of our will to live.

The American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (AAPI) says there are around 60,000 physicians, and 15,000 med students or residents of Indian heritage in the U.S. Up to 12 percent of all American med students have Indian roots.

Over recent weeks, many have received phone and video calls with bad news from home. An older relative, a family friend. A former classmate. Another funeral pyre.

“In this wave of the pandemic, it’s the young who are falling, who are filling the intensive care units,” Roy wrote. “When young people die, the older among us lose a little of our will to live.”