It was springtime in the Shenandoah Valley when Virginia’s first medical school went up in flames.

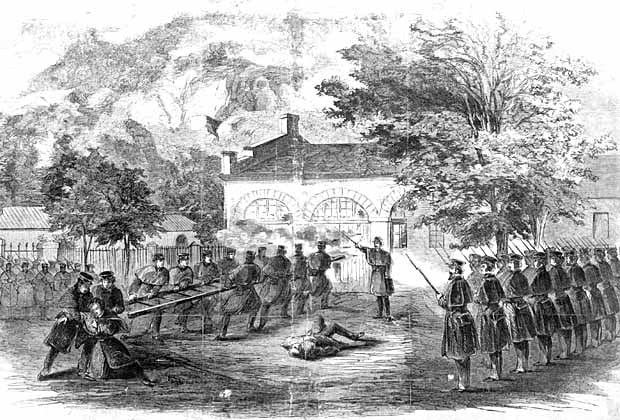

Ordered by a former Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, Union Army physicians and chaplains held up the torches and burned the school buildings to the ground.

The destruction of Winchester Medical College in May 1862 was the last, violent act of vengeance springing from one of the most controversial moments in American racial history.

A failed attempt at sparking a slave rebellion, John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia showed that violence had become inevitable when it came to resolving the issue of slavery in America.

Before the fiery abolitionist was hanged for leading his attempted “insurrection,” Brown famously declared that “the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood.”

In those days, if the students knew where they could get hold of a dead body not too long since departed from this mortal coil, the body was obtained, whether by fair means or [foul].

Those words would prove to be prophetic when, 16 months later, the American Civil War—a culmination of centuries of often violent debate over slavery—began. Yet it wasn’t Brown who lit the fuse that led to the destruction of the Virginia med school.

Prior to the outbreak of war, Winchester Medical College’s own students stole the bodies of two of Brown’s doomed raiders in its aftermath, including Brown’s own son Watson. Two others hanged for participating in the raid were later gifted to the school by Virginia’s pro-slavery governor.

Though not officially reported, desecration of the four bodies was likely. The practice of grave robbing for cadavers too, was rife.

Though little known, the story of Winchester Medical College reveals how much of the national tension—about to spill out into war—existed even in the hallowed halls of American medical education at the time.

Med school before the war

Though the first American medical school opened in the 1760s, only 13 existed by 1820. First chartered in 1826 as the ‘Medical College of the Valley of Virginia,’ Winchester’s early med school was the Commonwealth of Virginia’s first.

Initially, it operated for only two years before re-opening in 1847 as Winchester Medical College. Well-resourced for a pre-Civil War med school, it had “a surgical amphitheatre, two lecture halls, a dissecting room, a chemical laboratory, a museum, and offices.”

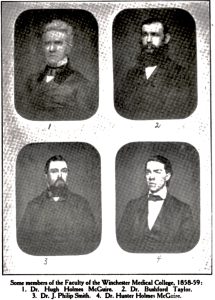

A notable surgeon thought to be one of the first to operate on clubfoot, Winchester’s Dr. Hugh Holmes Mcguire was one of the school’s founders. His son Hunter Holmes Mcguire would study at Winchester Medical College, later serving as the personal physician to Confederate General Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson.

Rare at the time, the Virginia legislature provided a portion of the school’s initial funding. At the time, most med schools were owned by faculty, who were paid directly by students.

When the War started in 1861, there were 63 medical schools open in the U.S. Of these, 16 were in states that joined the Confederacy. Only one—Richmond’s Medical College of Virginia, now the VCU School of Medicine—remained open throughout the war.

Despite the technological restrictions, some Southern medical schools experimented with concepts soon to become commonplace through medical education.

In the late 1850s, Georgia’s Dr. Joseph Jones became one of America’s first dedicated medical faculty members, researching tropical diseases. Though it folded at the start of the war, the New Orleans College of Medicine offered some of the first clinical clerkships in the late 1850s.

Despite the advances, gaining clinical and anatomical experience was always hard for pre-Civil War med students. In larger cities, students could visit hospitals to observe patients and fellow physicians at work.

In rural areas like the Shenandoah, small clinics were sometimes opened to provide this experience, though “patient contact was often limited to that of the preceptorship.”

A lack of preservation or refrigeration facilities meant finding cadavers to dissect was also challenging. Writing for the Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine in 2012, Dr. Robert Slawson wrote that several smaller med schools closed due to this, while others saw students use dogs in place of human bodies.

In both the North and South, stealing bodies—especially those of deceased slaves—was a relatively common practice in pre-Civil War medical schools.

In the South, many were provided by plantation owners when slaves died. Graverobbing of municipal cemeteries was also widespread. In 1878 in Cincinnati, the body of Rep. John Scott Harrison—the father of President Benjamin Harrison—was stolen by students from Ohio Medical College.

Though clearly unethical, the practice was largely legal at the time. Until 1884, when legislation was passed governing body supply, “grave robbing and body snatching were primary means of obtaining cadavers for medical school instruction” in Virginia.

“In those days, if the students knew where they could get hold of a dead body not too long since departed from this mortal coil, the body was obtained, whether by fair means or [foul],” Dr. William P. Mcguire wrote in Surgery, Gynecology, and Obstetrics, in 1937.

‘The chasm appeared unbridgeable.’

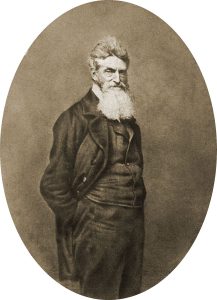

John Brown was a fitting public figure for pre-Civil War America. A staunch abolitionist who believed slavery could only be overthrown by violence, Brown was prominent in the ‘Bleeding Kansas’ clashes in the 1850s.

As the decade closed, Brown began working towards his long-held dream of fomenting a slave rebellion. Though he met with Black leaders like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman and found support amongst the Northern abolitionists, few wished to join his crusade. Douglass advised him against it.

On October 16, 1859, Brown and a band of 21 followers launched their raid on the federal munitions arsenal at Harpers Ferry, with plans of using the stolen weapons to arm the rebellion.

Five of his raiders were Black, a combination of former slaves and free men. Three others were his sons. They quickly took over the arsenal, took several hostages, and began a shootout with Harpers Ferry locals.

News of the raid traveled quickly, electrifying both the North and South. Slawson reported that more than 300 medical students left their schools in Philadelphia protesting against the raid “and returned to Southern medical schools.”

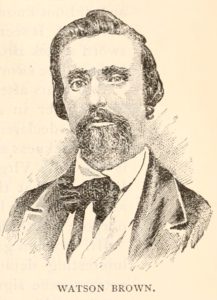

Within days, a company of U.S. Marines—overseen by future Confederate General Robert E. Lee—arrived in Harpers Ferry to quell the attempted rebellion. They made quick work of the raiders, killing ten and capturing seven, including Brown. Brown’s sons Watson and Oliver were amongst the dead.

“Goaded by curiosity and sensing opportunity,” a group of students grabbed a train from Winchester, a secessionist stronghold located just 30 miles southeast of Harpers Ferry, and headed into town.

Though the action was over before they arrived, the students came across the bodies of Watson Brown and Jeremiah Anderson—a deceased White raider—which they promptly collected and brought back to Winchester.

It is understood that the bodies were skinned and dissected, with the remains of Watson displayed in the school’s anatomical museum. “The whole [was] hung up as a nice anatomical illustration,” Louis De Caro, Jr wrote in Freedom’s Dawn: The Last Days of John Brown in Virginia.

Two months later, the bodies of Shields Green and John Copeland—two Black raiders hanged alongside Brown—were given to Winchester Medical College by Gov. Henry Wise (Winchester’s professor of anatomy had requested them). Both bodies met a similar fate.

Attempts to have the bodies of the four returned to their families were rebuffed by the school several times.

‘The glow of embers faded.’

A month after his doomed rebellion, Brown was found guilty of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. On December 2, 1859, he was hanged in Charles Town, Virginia.

Lee and Jackson—then an engineering professor at Virginia Military Institute—were both in attendance, as were future presidential assassin John Wilkes Booth and writer Walt Whitman.

“The tide of anger that flowed from Harpers Ferry traumatized Americans of all persuasions, terrorizing Southerners with the fear of massive slave rebellions and radicalizing countless Northerners, who had hoped that violent confrontation over slavery could be indefinitely postponed,” Fergus M. Bordewich wrote for Smithsonian Magazine in 2009.

“Before Harpers Ferry, leading politicians believed the widening division between North and South would eventually yield to compromise. After it, the chasm appeared unbridgeable.”

The Civil War erupted less than two years after the failed raid. It would visit Winchester several times during the conflict—changing hands several times—though Union troops first captured it in May 1862.

General Nathaniel Banks—a House Speaker in the mid-1850s—ordered its med school destroyed in retribution for the treatment of Watson Brown’s body, discovered when troops entered the museum. Banks’ soldiers also destroyed the house of James Mason, a prominent pre-War Senator who helped Virginia secede.

“The equipment and all records of the college were destroyed, and as the glow of the embers faded, the Winchester Medical College passed into history,” William Mcguire wrote.

The equipment and all records of the college were destroyed, and as the glow of the embers faded, the Winchester Medical College passed into history.

“[Banks] regretted it,” Winchester grad D.B. Conrad told James Monroe of Oberlin College, “but his New England doctors and chaplains did it — applied the torch with their own hands.”

Recovered from the med school museum before it was destroyed, a Union Army surgeon took the remains of Watson Brown back to his home in Indiana. They stayed there for two decades before being recovered by the Brown family in 1882 and buried near his father in upstate New York.

Despite speculation that remains were later found buried under a Virginia farmhouse, the bodies of Anderson, Green, and Copeland are still listed as ‘missing.’