Two weeks ago, the New York Times published an in-depth story on the distribution of a future COVID-19 vaccine, and how a federal committee is debating which groups within American society will get it first.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will prioritize crucial medical and national security officials, followed by other essential workers, the elderly, and those with underlying conditions.

Yet the Times revealed that the 53-person committee—of which only 15 have voting power—is considering giving the vaccine to Black and Latino Americans ahead of other groups.

As of June 12, 2020, the CDC showed that age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rates were highest amongst Black and Native Americans, five times that of white Americans. Latinx are four times as likely to be hospitalized as white Americans.

It’s racial inequality—inequality in housing, inequality in employment, inequality in access to healthcare—that produced the underlying diseases … it’s that inequality that requires us to prioritize by race and ethnicity.

According to the COVID Tracking Project, at least 28,856 Black Americans have died of COVID-19, 23 percent of the overall American total at time of reporting.

Numbers for Latinx and Native Americans were not known (USA Today reported in April that most federal officials and states aren’t tracking or releasing specific racial data on COVID-19 infected).

“Long-standing systemic health and social inequities have put some members of racial and ethnic minority groups at increased risk of getting COVID-19 or experiencing severe illness, regardless of age,” the CDC acknowledged.

The CDC says higher rates of chronic illness, especially heart disease and diabetes, and a higher chance of exposure due to employment that requires face-to-face contact, are reasons for the higher death toll amongst Black Americans. Almost every other American minority group faces similar challenges.

“Knowledge about the disparities in use of vaccines among ethnic minority patients is essential to eliminating disparities and creating pharmacy-based immunization practices that are effective in addressing barriers in these specific patient populations,” Dr. Anthony J. Patton wrote, in a 2017 paper on the use of immunization services amongst minorities.

Reasons for mistrust

Racial disparities in American healthcare are well-documented, with eagerness to be treated by new vaccines often downstream of clear mistreatment.

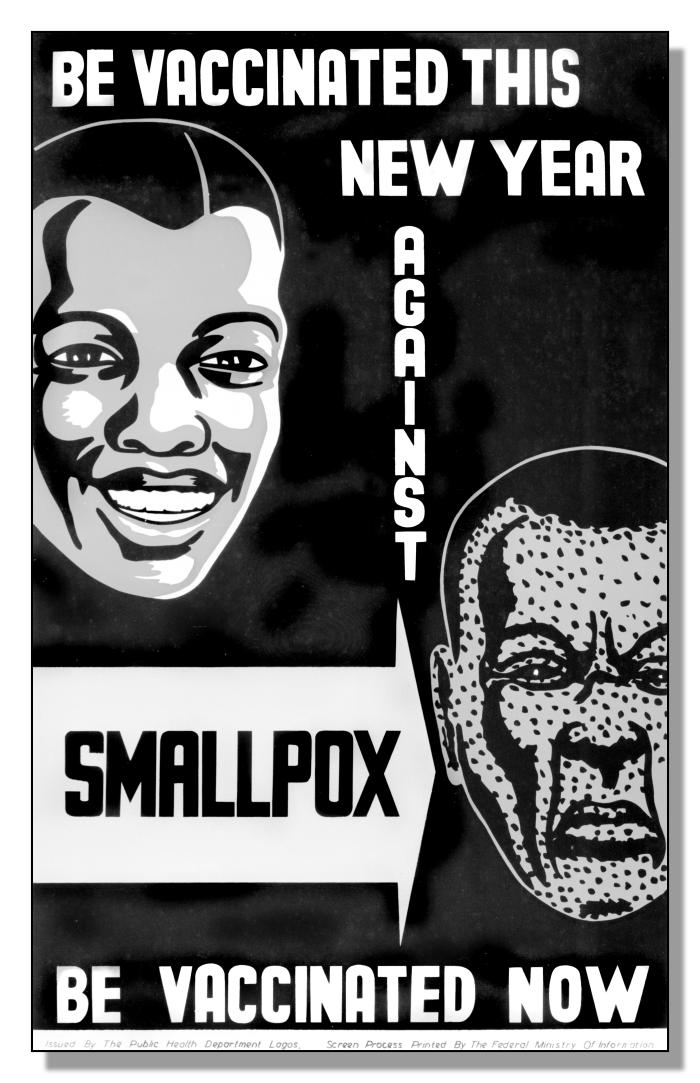

During a smallpox outbreak in the early 1900s, a Black community in Kentucky was forced, at gunpoint, to receive inoculations, while access to the polio vaccine, created by Dr. Jonas Salk in 1955, is seen as one of the first clear instances of racial disparities in vaccination distribution.

“As the fight against Jim Crow medicine grew more forceful in the 1950s,” Dr. Noami Rogers wrote in a 2007 study on the politics of polio, “Blacks—now recognized as susceptible to the polio virus and as deserving recipients of the advances of medical science—waited eagerly for their children to receive the Salk vaccine.

“But all too often, it was offered to children waiting on the lawn outside the local white school door.”

During the 1989-1991 measles outbreak in the United States, the Pharmacy Times reported that “[native] American, non-Hispanic Black, and low-income children had up to 16 times the risk of getting the disease than white children. The same groups were “recognized as being under-vaccinated.”

The shocking ‘Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment’ is often pointed to as the ignition of a long-standing distrust in government-recommended vaccinations amongst Black Americans.

Sold under the guise of free healthcare, the Experiment was a 40-year government study that kept hundreds of poor Black sharecroppers in rural Alabama uncured of syphilis.

By 1972, more than 120 had died of syphilis or related issues, while 40 wives had been infected, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis.

The study remains one of the most shocking examples of unethical medical experimentation in American history. To this day, Black Americans point to its existence as a reason for skepticism in the healthcare system.

For African Americans of a certain age group, Tuskegee always looms in our minds.

The New York Times reported that a recent Pew study showed 56 percent of Black adults would definitely, or probably get a future COVID-19 vaccine, compared to 74 percent of white and Latinx Americans.

Today, Black Americans are around 40 percent less likely to receive a flu vaccine than white Americans, and are almost twice as likely to have no health insurance (Latinx Americans are almost three times as unlikely).

By 2003, Dr. Leonard E. Egede, who co-authored a study into minority healthcare, believed gaps in vaccine coverage had their stimulus in both patients, and physicians.

“Minority patients often don’t want the vaccines because they are more likely to mistrust their doctors or have been misinformed on their benefits,” he says.

“But physicians may not be offering vaccinations to their minority patients as often as they do for white patients. And even when they do and the patients refuse them, they don’t make as much effort to convince them to get the shots.”

Improvements in vaccination rates

Improvements have been made. Spurred on by the 1989-1991 measles outbreak, the Vaccines for Children (VFC) was started to close rates of under-vaccination in 1994.

The programme saw the CDC buy discounted vaccines and provide them to state health departments, and local health agencies, to cover as many historically disadvantaged children as possible.

It worked. A 2014 CDC study showed that, for vaccines recommended since 1995, disparities in vaccination coverage between white American children and those from other racial groups have declined across the board.

The same rings true amongst adults with 2015 data from Health and Human Services showing that, outside flu treatment, vaccination rates have largely stabilized amongst Black and white Americans.

With a COVID-19 vaccine possible by early next year, and the U.S. Government recently agreeing with Pfizer to distribute an initial 100 million doses, the politics of vaccine distribution are an issue soon to emerge on our horizons.

As in the past, race will play a huge role.

“It’s racial inequality—inequality in housing, inequality in employment, inequality in access to healthcare—that produced the underlying diseases,” Dr. Dayna B. Matthew of George Washington University told the Times.

“That’s wrong. And it’s that inequality that requires us to prioritize by race and ethnicity.”