A former bawdy frontier town located in Great Plains cattle country, Miles City, Montana seems an unlikely place for the story of the world’s greatest vaccinologist to begin.

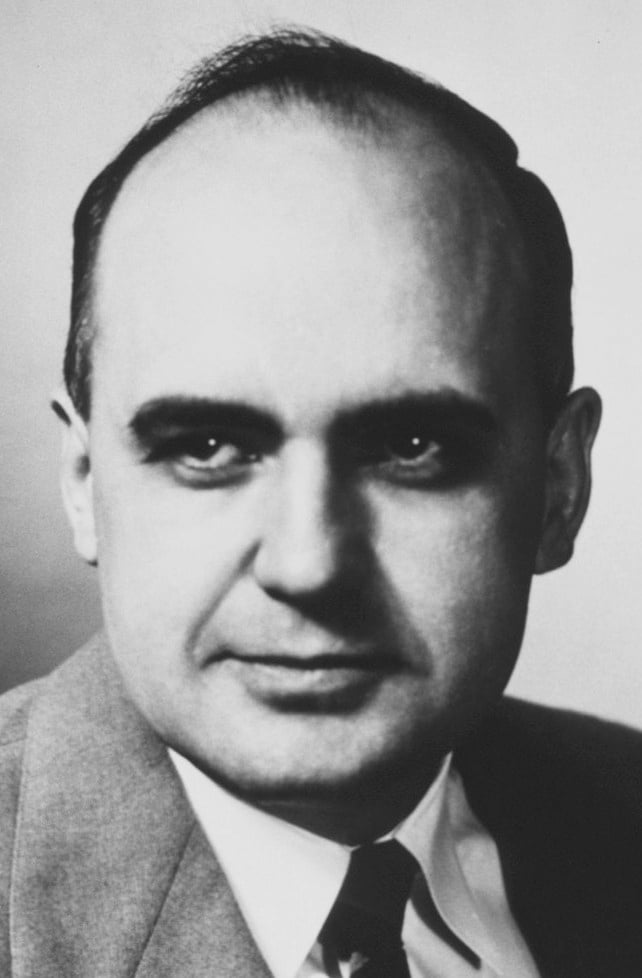

Yet when you factor in a hardscrabble farm upbringing in the years following the largest pandemic of the last hundred years, the origins and drive of Dr. Maurice Hilleman—who created more than 40 important vaccines, including those for measles, mumps, chickenpox, rubella, hepatitis A and B, and meningitis—make a lot more sense.

His discoveries have probably saved tens of millions of human lives, with children the biggest benefactors of his long list of contributions to improving our understanding of controlling disease.

Among scientists, he is a legend. But to the general public, he is the world’s best kept secret.

Though a notoriously prickly man to work alongside, it remains remarkable that few outside the scientific community are aware of his incredible story, which includes his discovery of the mumps vaccine with samples taken from his own daughter, and his stopping of the 1957 flu pandemic in its tracks.

“Among scientists, he is a legend,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told the Washington Post in 2005, when Hilleman died, aged 86.

“But to the general public, he is the world’s best kept secret.

“I think, without hyperbole, he as an individual has had a more positive impact on the health of the world than any other scientist, any other vaccinologist, in history.”

Tough upbringing

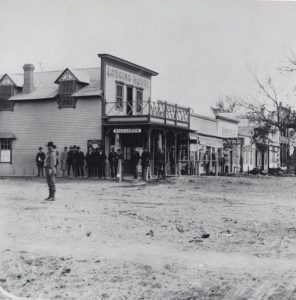

Hilleman’s hometown demands its own mention before the trajectory of its most famous son plays out.

Originally based around a frontier fort well-known for drunkenness, Miles City, located in Custer County, came to life in the 1880s after relocating two miles away from the old army barracks.

Though not formally documented, Guinness World Records recognizes the biggest snowflake—15 inches across—as having fallen there, in January 1887.

Hilleman was born into tragedy on August 30, 1919 on a farm just outside Miles City, with his mother and sister dying due to the birth. Juggling seven other children, his father sent young Maurice to live on his uncle’s farm.

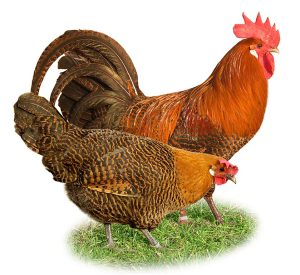

It was a tough upbringing that saw Hilleman take a special interest in chickens, which would later prove useful as he weakened live viruses, and developed vaccines, in chicken eggs.

“Montana blood runs very thick,” Hilleman once said, “and chicken blood runs even thicker with me.”

After working at a drugstore, the Montana farm boy eventually studied at Montana State University and the University of Chicago in the late 1930s before developing his first vaccine in World War II to protect American troops against Japanese B encephalitis in the Pacific.

Montana blood runs very thick, and chicken blood runs even thicker with me.

Upon receiving his doctorate in microbiology and chemistry, Hilleman told his dubious professors, who wanted him to stay in academia, that he intended to work in industry as it provided the best opportunity for “ensuring and expediting clinical applications.”

“His commitment was to make something useful and convert it to clinical use,” Dr. Paul Offit, the chief of infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told the British Medical Journal.

“Maurice’s genius was in developing vaccines, reliably reproducing them, and he was in charge of all pharmaceutical facets from research to the marketplace.”

Stopping pandemics, and creating vaccines

Hilleman made his first massive vaccine breakthrough in 1957, while working, a little ironically, at the Walter Reed Institute of Army Research near Washington, DC.

Beginning in China, a H2N2 bird flu pandemic was beginning to sweep the world with up to a million lives thought lost by 1959.

Working nine straight 14-hour days to isolate the virus, Hilleman and his team were able to prove H2N2 was a whole new strain of flu. They also found that there was virtually no American immunity to it, meaning the pandemic could have potentially disastrous consequences in the U.S.

Working with chicken breeders to acquire otherwise slaughtered roosters to fertilize millions of eggs, Hilleman developed a flu vaccine that was available in limited numbers by late 1958.

Offered a massive salary by pharmaceutical giants Merck, the Montanan went private in 1957, resulting in four ground-breaking decades of vaccine study as their director of virus and cell biology research.

By the time Merck forced him to retire in 1984—like legendary cardiologist Dr. Paul Dudley White, he kept his desk and continued as a ‘consultant’—the company had gained 37 vaccine licenses, with another three on the way.

His development of a measles vaccine in the early 1960s involved his chicken connection again, before his work to create the first mumps vaccine came when his daughter Jeryl Lynn contracted it in 1963.

“[Hilleman] took a culture from her throat, immersed the swabs in beef broth and took them to the laboratory freezer in the middle of the night,” the Post reported, in 2005.

Hilleman used to say that when you are making a vaccine, start with feasibility, ease of distribution, and availability and safety.

“He later used the specimen to isolate the mumps virus, grow it in the cells of chicken embryos and produce a very weak version of the virus, enough to trigger the body’s defense and immunize whoever took the vaccine. He named it the Jeryl Lynn strain, after that daughter.”

The MMR vaccine, in widespread use today, would follow in the early 1970s. According to the New York Times, up to a billion children have received the MMR vaccine this century, “preventing 9.6 million deaths from measles alone, for less than $2 a dose.”

Still alive today, Jeryl Lynn is now a financial consultant to Silicon Valley biotech companies.

A crucial element in his discoveries, chickens also benefited from Hilleman’s work. In 1971, the Los Angeles Times wrote, he created a commercial vaccine for Marek’s disease, a viral infection causing lymphoma in chickens. Hilleman would save the poultry industry, millions.

“I figured I owed it to the chickens,” he said.

Character and legacy

Described by the BMJ as “an often harsh, impatient fellow who tangled with industry and government bureaucracies,” Hilleman argued that politics too often stood in the way of science’s ability to improve public health.

“He has this irreverent, no-nonsense, let’s-get-it-done attitude that perfectly complemented a highly sophisticated intellect,” Fauci told the Post.

Despite his belligerent character, Hilleman’s legacy continues today in the fight to treat COVID-19. Merck, Hilleman’s old employers, has a COVID-19 vaccine on the cusp of Phase III clinical trials in the U.S.

Recently, his approach to vaccines was cited by Dr. Robert Gallo, a prominent virologist and co-discoverer of HIV, who supports using the oral polio vaccine as a ‘stop-gap’ measure against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, until an effective vaccine is found.

I would do it over again because there’s great joy in being useful, and that’s the satisfaction that you get out of it. Other than that, it’s the quest of science and winning a battle over these damned bugs.

“Hilleman used to say that when you are making a vaccine, start with feasibility, ease of distribution, and availability and safety,” Gallo said, in a recent interview with Eureka.

While the pragmatism and tough edges required of being a Montana farm boy might have made life harder for those who worked with him, it is the world’s great fortune they also enabled Hilleman to make the remarkable discoveries that he did.

“Well, looking back on one’s lifetime, you say, ‘Gee, what have I done — have I done enough for the world to justify having been here?,’ he once said.

“That’s a big worry — to people from Montana, at least. And I would say I’m kind of pleased about all this.

“I would do it over again because there’s great joy in being useful, and that’s the satisfaction that you get out of it. Other than that, it’s the quest of science and winning a battle over these damned bugs.”