In light of how much has changed since the dawn of human history, it’s easy to overlook how similar we are to our ancient ancestors, and how we would have likely drawn the same conclusions they did.

Like them, we continually seek to understand the world around us. Indeed: finding patterns in the changes and movements of the natural world is part of human nature. We seek reasons for why they are happening, and ask ourselves, “okay, what’s next?”

The period we’ll now explore was very much a time when people saw no delineation between art and science.

Today, these explorations are often done through what would be classified as either scientific inquiry or artistic expression. One of the big themes we set in the introduction to this series was that art and science are united or split at different points in history.

The period we’ll now explore was very much a time when people saw no delineation between the two pursuits.

They were seen as inseparable parts of a whole and were equally employed to try and answer those big human questions about who we are, where we belong, and where we’re going.

Prehistory

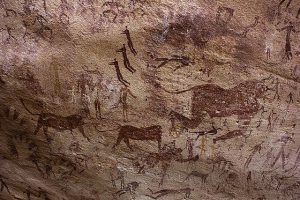

It’s no wonder that we can find the roots of medical illustrations as far back as our records go. We can look all the way back to the cave drawings and sculptures that early humans made of the animals they encountered and of their own form.

Were they early forms of artistic or religious expression? Were they attempts at creating models to instruct and understand? Or both simultaneously? Their voices are lost to the ages; there’s no way to know for sure.

Ancient Egypt (3,100 BCE – 332 BCE)

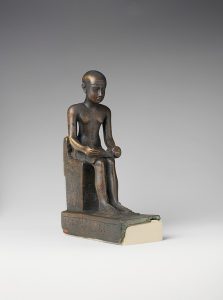

What we do know is that about five thousand years ago, Imhotep—an ancient Egyptian engineer, physician, and advisor to Pharaoh Zoser—launched a medical revolution by positing that healing is not something to be left to magic and the gods, but to observation, diagnosis, and treatment. His influence would last millennia.

Imhotep’s impact on healing was so profound that ancient Egyptians would come to deify him as the god of medicine. It’s easy to see now how his emphasis on observation and understanding was such a huge step forward in the history of medical illustration.

Hellenistic Greece (323 BCE – 30 BCE)

For our next step in our journey, we head back to Egypt about three thousand years after Imhotep, to the city of now Greek-ruled Alexandria.

Thanks to King Ptolemy, who ruled from 323 to 282 BCE, founding the Alexandrian Museum and the Great Library of Alexandria—which he mandated would be a “collection of all books in the inhabited world”—the city became the center of art and scholarship in the known Western world.

Naturally, the Great Library attracted poets, philosophers, musicians, historians, mathematicians, and scientists from all over. Discussing the fruits of this scholarship and sharing of knowledge could fill libraries itself today.

We’ll focus on the three who had a profound impact on shaping the future of medical illustrations: Herophilus (330-260 BCE), Erasistratus (304-250 BCE), and Galen (130-200 CE; technically of Rome, but heavily influenced by the physicians of Alexandria).

To facilitate understanding, Ptolemy lifted prior taboos on dissections, and the medical school there became the vanguard of the scientific study of medicine as a result.

To facilitate understanding, Ptolemy lifted prior taboos on dissections, and the medical school there became the vanguard of the scientific study of medicine as a result.

Herophilus and Erasistratus took full advantage of this newfound freedom, and, eschewing the prior traditions of physical observation and disease descriptions, provided precise descriptions of anatomy and physiology.

With the decline and eventual fall of the Great Library, all of the writings of these two medical pioneers were lost, though, fortunately, a number of their interpretations were preserved in the works of Galen.

Building on the work of Heriphilus, Galen wrote hundreds of important medical treaties. In compiling them, he incorporated some of the work of those before him, as well as adding in new observations and theories. The role of arteries was ascertained, while the then-mystery of circulation began to unravel.

Galen’s work essentially founded the experimental method of medical research. It would remain relevant for 1500 years, after his death around 210 CE.

Despite the lack of surviving sketches or illustrations, the works of Herophilus, Erasistratus, and Galen stood the test of centuries of thought, inspiring further study in the Islamic world, Byzantine Empire, and amongst early Medieval European scholars.

Byzantine era (330 – 1453 CE) and the Islamic World

While Europe struggled for direction after the fall of the Roman Empire, the Islamic world was flourishing. Academics in Persia and surrounding areas copied and preserved the knowledge of the Great Library, and made many of the earliest surviving medical illustrations.

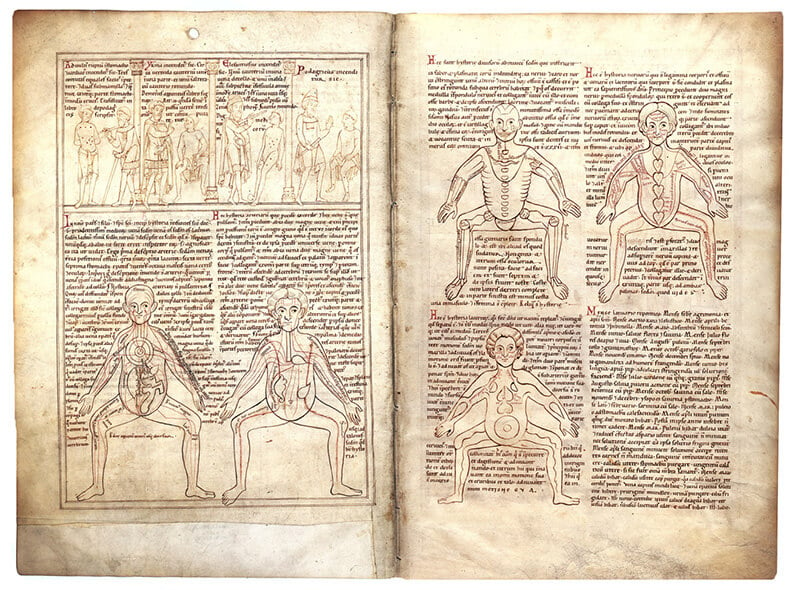

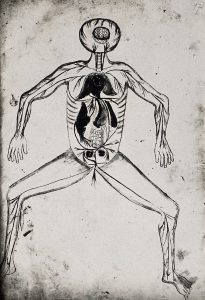

Called the “five figure series,” many of the illustrations were based on the work of Galen. They are believed to have been copied from a much earlier source, lost to time.

Artistically, these drawings are rather awkward to modern sensibilities. They predate the rediscovery of perspective, and were flat, showing the subject in a squatting pose with their limbs splayed.

Still; parts of the body are identified and labeled in a manner comparable to today.

Up next: The Renaissance and The Age of Enlightenment

The images and concepts in the next installment of this history of medical illustrations will likely look and sound a lot more familiar to our modern senses.

While the fusion of art and science yielded perhaps its most stunning—and, frankly, beautiful—discoveries, the pace of innovation and inquiry drove a wedge between the two pursuits that we still live with today.