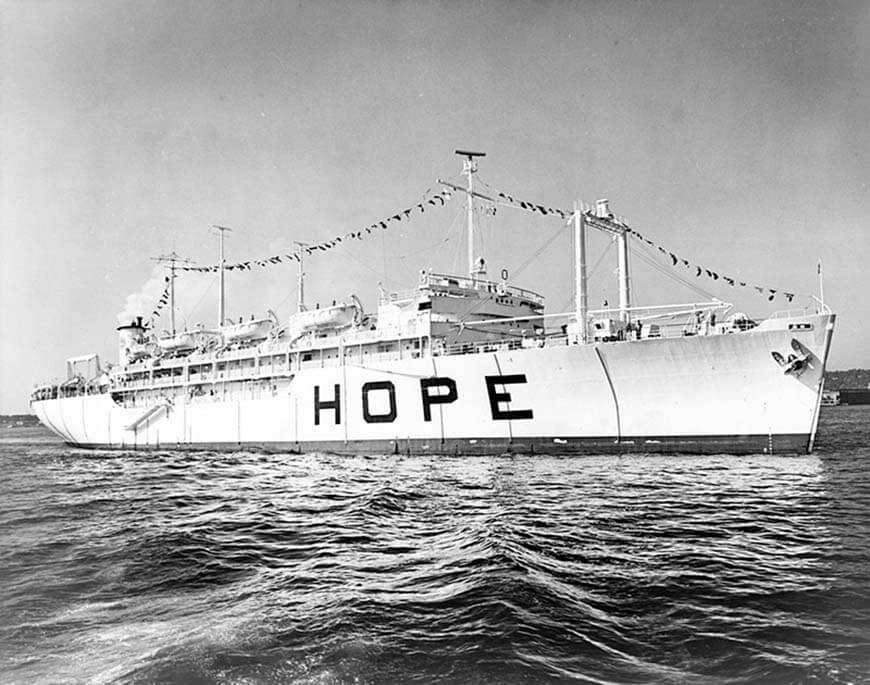

For hundreds of thousands of people around the world, their introduction to ‘hands-on’ American medical care came in the form of a big white ship, with HOPE written on its sides.

Graham Greene—the English author who perhaps best captured the Cold War—couldn’t have written a better metaphor for the United States foreign policy in the 1960s, himself.

Initially funded by the State Department alongside large corporate interests, the SS Hope floated the world’s seas, delivering medicine and support in countries like Indonesia, South Vietnam, Nicaragua, Colombia, and Brazil.

Despite its extremely limited capacity for significant impact on local health care, Hope was a powerful symbol of ‘American values’, that helped grow U.S. geo-political influence abroad, while being used as a rallying cry domestically.

Indeed: the uneasy mix of public and private interests, which included a prominent Detroit turbine engine and tool manufacturer, surely saw the early years of Project HOPE (Health Opportunities for People Everywhere) in consideration for medicine’s ‘Ugly American’ award.

Their story was non-controversial, simple, and packaged as an emotional appeal: skilled American doctors, armed with the technology, take up a vague goodwill mission of healing sick children and teaching medical science.

Yet the clear public health good that was achieved, is undeniable.

Upon Hope’s return from Brazil in 1974, where it had spent the previous two years, it is thought that around 2500 American doctors, nurses and medical technicians served on it.

All up, around 200,000 people were treated for various ailments and nearly 19,000 major surgeries were performed, while around 9,000 local medical students were trained.

That legacy, and its continuing efforts today providing medical support following natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic, ensure Project HOPE fractures the lens of easy definition.

“Their story was non-controversial, simple, and packaged as an emotional appeal: skilled American doctors, armed with the technology, take up a vague goodwill mission of healing sick children and teaching medical science,” Teresa Logue wrote for The Yale Review of International Studies, in a magnificent 2013 essay on Hope.

“This glossed over the complicated nature of American foreign relations, especially in the countries Hope visited. Thus, Project HOPE earned the hearts of the American people, but, in its simplicity, it also discouraged and prevented critical dialogue about American foreign aid.”

Dr. Walsh’s dream

Historically used to care for the wounded of a nation’s own military, the use of hospital ships to help other countries rebuild following World War II, and deal with continuing natural disasters.

After seeing the effect improved medical access had on Pacific Islanders during the war, New York’s Dr. William B. Walsh “envisioned a floating medical center that would bring health education and improved care to communities around the world.”

A medical officer aboard a U.S. Navy destroyer, he was the first American physician to enter Hiroshima after the city was flattened by the world’s first atomic bomb.

In 1958, Walsh pitched his idea to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, convincing him of the public relations potential it held for America abroad.

“There are a lot of people who don’t understand Americans and a lot of people who don’t like Americans,” he reportedly told Eisenhower.

“In fact, there’s a book called ‘The Ugly American.’ And, Mr. President, with great respect toward you, this is not going to be solved by heads of state.”

Thomas S. Gates, Eisenhower’s Secretary of the Navy, was enthusiastic. The USS Consolation, a mothballed ex-WW2 hospital ship, was made available for a dollar-a-year charter.

There are a lot of people who don’t understand Americans and a lot of people who don’t like Americans.

Initially denied State Department funding due to the project being “too symbolic and not practical enough in nature”, Walsh leveraged big corporate backers into lobbying the federal government to pay to recondition the ship, before filling it with volunteer doctors and nurses, and medical supplies.

Detroit’s Ex-Cell-O, who’d later fund an Oscar-winning short documentary about Project HOPE, was a big supporter. Famed actor George C. Scott’s father served as a vice president at the company.

‘Hope’ floats

Reaching Indonesia in late 1960 with 100 doctors and 150 nurses aboard, Hope’s first voyage was a public relations success, receiving significant public and political attention back home.

Consistent USAID funding was guaranteed by both major parties, while start-up volunteer organizations began to fundraise for Project HOPE on a community level.

The 130-bed Hope was well-stocked. Along with three operating rooms, a pharmacy, an isolation ward, a radiology department, there was room-to-room closed circuit television, so local doctors and students could watch operations and other procedures.

Actually, if the ship were simply a service ship, it would not be worth sending to any country, because the countries to which we go have such enormous problems of health that a 130-bed hospital … couldn’t possibly, in ten months, begin to dent the problems.

Bankrolled by dairy industry interests, an innovative water plant that blended powdered milk and fats, creating 1000 gallons of milk a day, was also on board, featuring extensively in Ex-Cell-O’s Oscar-winning short.

Yet on the ground, volunteer doctors and nurses were quickly finding that the limits of their capacity, beyond the feel-good factor of their presence.

“Actually, if the ship were simply a service ship, it would not be worth sending to any country,” Dr. Walter C. Rogers, a volunteer doctor, wrote, after a 1966 voyage to Nicaragua, “because the countries to which we go have such enormous problems of health that a 130-bed hospital … couldn’t possibly, in ten months, begin to dent the problems.”

“Our only hope is to train people in all sorts of medical and paramedical fields to go back and train other people in their own country.’

When rising operational costs ended Hope’s trips abroad in 1974, Project HOPE transformed into a land-based organization.

It played an important role in building public health networks in post-Soviet states in the 1990s, and has had a presence in virtually every war zone, or region affected by natural disaster since. This month, Project HOPE was quick to provide medical support to Beirut, in Lebanon, following the massive August 4 port explosion.

As part of the worldwide fight against COVID-19, the organization says it has distributed more than 8.9 million pieces of personal protective equipment in 110 countries, and provided pandemic training for over 62,000 health care workers. Assistance has been provided domestically, especially in Houston.

A complicated legacy

A $85 million operation today, the organization receives more than $20 million in government funding with the majority coming from wealthy benefactors, corporate gifting, and foundation grants.

Though recently put up for sale, it is based out of Carter Hall, a 200-year-old former plantation house in Northern Virginia that once served as a headquarters for famed Confederate Gen. Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson.

Nearly sixty years after Hope first sailed, the use of medical soft power still persists around the world. U.S. naval hospital ships Comfort and Mercy have been deployed throughout Latin America over recent years, and are now helping with the COVID-19 crisis in the U.S.

The Chinese naval hospital ship Daishan Dao has made regular Hope-like visits around the world over the last decade, renaming itself Peace Ark when it does.

“The story of Project HOPE testifies to the muddling of humanitarianism with agenda, in the process of making a national symbol,” Logue concluded.

“Essentially, this tangling was made possible by the simplicity of the initially emotionally attractive idea. It forms a cautionary tale for development organizations seeking mass appeal, today.”