When Eric Gantwerker was growing up in Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s, he and older brother Brian were passionate video gamers.

Atari and Nintendo NES were their prime consoles, with Metroid, Street Fighter, and, later on PC, Dragon Wars, counting amongst their favorite cartridges and discs.

Though the Gantwerker brothers—both of whom would later train as doctors—grew up in an era that set an enthusiastic tone for coming technological change, surely neither could then imagine the extent to which gaming and medicine might merge.

“When people think video games, they think simulation, they think virtual surgery – and a certain image pops up in their mind,” Dr. Gantwerker—now the Vice President/medical director at Level Ex, one of the world’s leading medical game companies—says.

Games are not just for our kids playing Minecraft in the basement. [They] have tremendous power and ability if harnessed appropriately.

“The best feeling I have is when they look at our stuff and it blows up all those preconceived notions.”

After clunky beginnings nearly 40 years ago, medical gaming has been carving out a growing niche within medicine. Recent steps forward in virtual (VR) and augmented reality (AR), along with the increasing shift to mobile devices over the last decade, have helped fuel a rise brought into even sharper relief by in-person Covid-19 restrictions.

Likely worth around $20 billion now, healthcare gaming, which includes fitness apps, is expected to be a $40 billion industry by 2024. For future doctors and gamers alike, medical gaming companies such as Level Ex and Osso VR sit on its cutting edge.

Last June saw the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approve its first ever video game as a prescribed medicine for children, while a chorus of voices within medicine have long talked up video games as providing beneficial treatment options for sufferers of depression, autism, and even Alzheimer’s disease.

Though more than 100 American med schools already offer certified simulation centers—largely put out of action due to the pandemic—medical games offer the ability to learn more away from the classroom, long before students get in front of actual patients.

Gantwerker says medical gaming has “tremendous power” to alter medical education if preconceptions can be navigated.

“Games are not just for our kids playing Minecraft in the basement,” he says. “Games have tremendous power and ability if harnessed appropriately.

“I think that medical education will change in respect of using that technology, using the game psychology, and having people actually making [medical] games for themselves.”

Remember ‘The Surgeon’

The earliest medical video games popped up in the early 80s, with Imagic’s ‘Microsurgeon’ likely the first to ever put the doctor’s gloves on a gamer in 1982.

Hospital and emergency management have largely dominated the genre. Released by Maxis on MS-DOS in 1994, SimHealth: The National Health Care Simulation saw gamers balance politics and policy as they attempted to design a functioning healthcare system.

It became available around the same time President Bill Clinton’s own national plan was being debated in congress, which, eventually, failed to pass. “SimHealth’ is almost too real,” David Colker wrote, for the Los Angeles Times. “Play it and you’ll soon be saying, “there must be a better way.”

Only a handful of games have attempted to portray the high-stakes realism of surgery, starting with The Surgeon. Designed by Dr. Myo Thant, a Baltimore oncologist and computer scientist, and available on Amiga and Macintosh in 1985, The Surgeon presented gamers with patients to diagnose, prescribe medicine to, and even operate on if needed.

A 14-page manual and surgery ‘cheatsheet’ was provided if the scrubs needed to come out. The lack of a ‘save option’ meant that, during surgeries, like in the real world, mistakes could be fatal.

Though infamously bug-ridden, Legacy’s eight-game Emergency Room series took it a step further. Between 1998 and 2010, gamers could be promoted from med student or resident, all the way up to hospital ‘chief of staff,’ depending on the successful completion of treatment plans for hundreds of varied patient cases.

Despite the early advances, an industry-wide embrace of medical games has been slow in coming.

Bayer did produce an FDA-approved glucose meter in 2010, which, through encouraging children to test their sugar levels, awarded ‘points’ on a Nintendo DS game. In 2015, two Boston-based medical gaming companies were pressuring lawmakers to get games recognized as potential treatment options for physicians.

One of them, Akili Interactive, developed EndeavorRX, last year’s groundbreaking FDA-approved game. The iPad-based game can now be prescribed to help children aged between 8 and 12, with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Citing Xbox Kinect’s infra-red sensors and Nintendo Wii’s motion sensors (both were on the gaming market by 2010) as recent evidence, Gantwerker says medicine has lagged behind gaming when it comes to the effective use of new technology for decades.

People at the highest levels of medical education have to change their mindset to understand what medical games actually are.

“Medicine is a very traditionalistic speciality,” he says. “It [has been] very slow to adopt technology – and gaming is no different.

“What your mental concept is of games is not what medical gaming is, it’s not serious gaming is – it’s not what these software-based simulations can do. People at the highest levels of medical education have to change their mindset to understand what medical games actually are.

“There is a lot to learn from the technology, and advancements and utilizations of that technology. You think about the arcade to the console, to mobile and the cloud; that was done by games a long time ago.

“Yet medicine is still beholden to physical locations for learning. We’re 20 to 30 years behind the gaming industry.”

Needs and outcomes

Like most things in life, recent improvements to medical gaming over have been inspired by a clear need.

Justin Barad, founder of Osso VR, told the Washington Post last year that the catalyst behind its orthopedic-centric VR simulations came from his time as a resident in Los Angeles, where colleagues would watch ‘last-minute’ YouTube clips to prepare for surgery.

“If there was a way, kind of like in the Matrix where you just plug in for five or ten minutes and refresh yourself, or get up to speed and then assess and make sure you’re ready to go, that would be a total game changer and have a massive impact on patients and the health care system as a whole, all thanks to video game technology,” Barad told the Post.

Level Ex also had its genesis in a purely medical need. The company was founded by Sam Glassenberg in 2015, when his father, a Chicago anesthesiologist, wanted to train on flexible fibre-optic intubation.

A leading film-inspired game developer in Los Angeles, Glassenberg got a free app up and running within weeks. More than 100,000 downloads followed over the next two years.

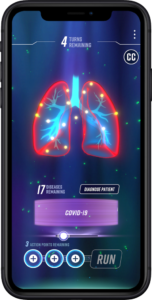

Now more than half a million medical professionals use Level Ex games, with rigorous medical oversight provided by the likes of Gantwerker. Its smartphone-run simulations allow users inside the human body, as they solve increasingly challenging patient cases.

So far, Level Ex’s various titles concentrate on pulmonology, gastroenterology, anesthesiology, and cardiology, as well as a Covid-19 specific one. Gantwerker says more are on the way, with a dermatology-specific game close. Two years ago, Level Ex linked arms with NASA to develop a virtual simulation to show the impacts of zero gravity on human anatomy and medical procedures.

In-game tweaks and changes are ongoing. Though still impressive, high fidelity graphics have been de-emphasized in recent iterations, with cognitive-based skills like judgment, decision making, and deductive reasoning receiving more of a focus.

Before heading to Level Ex, Gantwerker studied technology and simulation in medical education at Harvard Medical School (the Chicagoan names ‘What Video Games Have To Tell Us About Literacy and Learning’ by James Paul Gee as one of the books that changed his life). The impact of game theory on Level Ex’s titles has been important, he says.

“We’ve opened that funnel to the world of game mechanics, and probably de-emphasized a lot of the procedural based stuff, which we know we can do – it’s still in our tool chest – but it’s not the answer to everything,” Gantwerker says.

Med school impact

While measuring the usage of The Surgeon or Emergency Room by previous generations of med students is now virtually impossible, it’s almost certain the games inspired future careers in medicine.

Even if they didn’t, future med students who are also gamers have had a leg up on their colleagues for a while now. A 2007 study explored the potential link between video game play and successful laparoscopic surgical skills, finding that residents and physicians who were also gamers made around a third less mistakes in training than those who weren’t.

“Training curricula that include video games may help thin the technical interface between surgeons and screen-mediated applications, such as laparoscopic surgery,” the study’s authors wrote. “Video games may be a practice teaching tool to help train surgeons.”

Medical simulation centers were the first step forward into the world of VR and gaming at med schools, with more than 100 accredited by the Society for Simulation in Healthcare.

Featuring acute and critical care facilities that incorporate ‘smart’ dummies, the Johns Hopkins Medical Simulation Center in Baltimore is recognized as one of the best.

Though a step in the right direction, the simulation centers are far from perfect. Expensive and bulky, most lack the graphics of recent medical games and, requiring intimate in-person co-operation, have largely stood dormant during the Covid-19 pandemic. Barad described surgical training as “primitive” to the Post, adding it was “heavily reliant” on learning through observation.

With simulation centers out of action, Gantwerker says interest in medical gaming has quadrupled in the last 12 months. “There were deficiencies in the medical education systems that we’ve known have existed for many years,” he says.

“One of those is the idea of active learning, versus passive learning. The other is the idea that education [takes place] at a certain location, and that practicing on patient care had to happen in a physical location.”

First developed in the early 2010s, Holland’s VirtualMedSchool has been a good step towards more flexible remote learning, and is now used in 40 percent of all Dutch hospitals and med schools.

… medicine is still beholden to physical locations for learning. We’re 20 to 30 years behind the gaming industry.

The road from Metroid and Street Fighter to medical games in space might seem like a crazy one, but traveling it as he received his own medical education has certainly handed Gantwerker a ‘controller’ in his industry’s future. Better doctors through gaming? Why not, Gantwerker asks.

“[It’s] the idea that people can train at home, [it’s] the idea that people can have self-contained education that’s active versus passive,” he says.

“Using all this different software, including virtual reality, including augmented reality, including your phone – all of these types of things we need to develop, and I think they will be integrated into the medical education system going forward. They need to.”