On March 6, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson delivered a special address to the United States Congress on the plight of Native Americans.

Identifying indigenous people as “forgotten Americans,” Johnson illustrated the extreme difficulties they suffered in proportion to different demographic groups.

Amongst other social and economic differences, native unemployment was ten times the national average in the late 1960s, while only half of indigenous students finished high school.

Disparities in health care were just as stark. Infant mortality soared over other groups, while rates of almost every illness, especially tuberculosis, did too.

“Our goal is first to narrow, then to close the wide breach between the health standards of Indians and other Americans,” Johnson, who used the speech to promote a range of indigenous-focused public policy proposals, said.

The COVID-19 impact

Despite Johnson’s aims, more than fifty years later, the health care struggles of Native Americans continue at a level beyond virtually all other groups within the U.S.

As much as any recent Native American public health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed once more the enduring disparities.

I feel as though tribal nations have an effective death sentence when the scale of this pandemic, if it continues to grow, exceeds the public resources available.

Though COVID-19 data on races and ethnicities is not routinely recorded by hospitals or states, a recent New York Times report showed that the rate of cases in the eight counties with the largest numbers of Native Americans was almost double the national average.

These regions are the homes of one in six Americans who describe themselves as non-Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native. There are more than 5.2 million native Americans in the U.S.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that the age-adjusted coronavirus hospitalization rate for indigenous Americans are more than five times that of non-Hispanic white citizens.

Though total deaths are unclear, the Indian Health Service (IHS) says, as of Tuesday, 33,898 Native Americans have contracted COVID-19 (the Navajo Nation have been the worst hit, with 10,638 cases). The overall figure is more than the total number that have been infected in Australia and South Korea, combined.

“I feel as though tribal nations have an effective death sentence when the scale of this pandemic, if it continues to grow, exceeds the public resources available,” Fawn Sharp, the President of the Quinault Indian Nation, told the Times.

From smallpox epidemics to the IHS

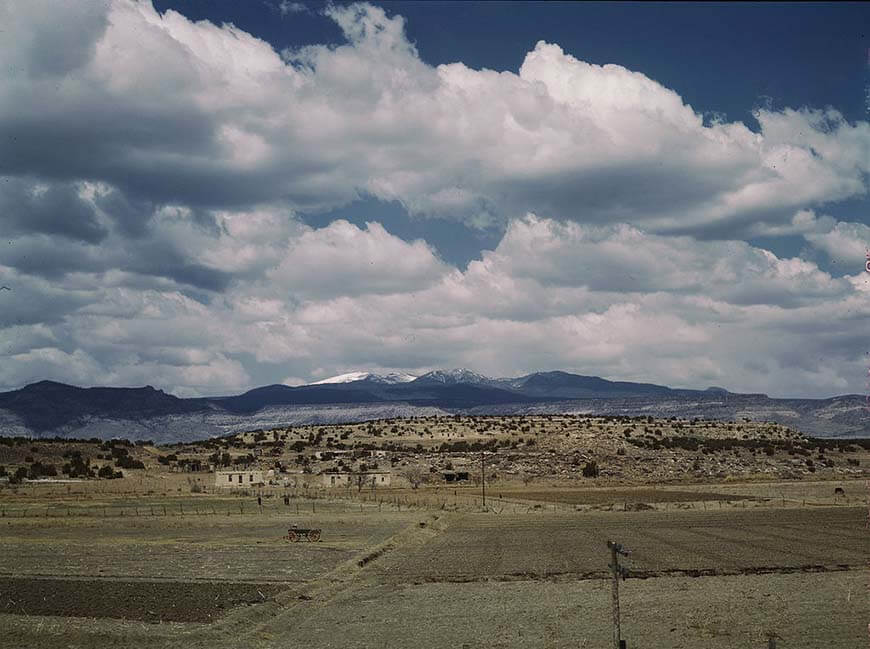

Across the Americas, indigenous peoples suffered greatly from virgin soil epidemics like measles, smallpox, and yellow fever, from when Europeans first arrived more than 500 years ago.

Before and after independence, it was no different in the U.S.

Smallpox swept across the continent in the late 1770s, with almost every tribe affected, particularly in the Pacific Northwest. More than 11,000 around today’s coastal Washington state are thought to have died.

In 1837, the disease came back aggressively on the northern Great Plains. By the end of the decade, the Mandan, Assiniboine and Niitsitapi tribes were nearly wiped out by smallpox.

Total numbers killed are virtually certain to be much higher than the estimated 17,000, not including its return in 1851.

Feelings that the disease was either intentionally spread, or spread by the carelessness of Upper Missouri river boat captains, began to simmer, helping broaden the distrust towards non-native Americans.

While the Office of Indian Affairs (now the Bureau of Indian Affairs) oversaw vaccination and public health programmes from the 1830s onward, the Snyder Act of 1921 marked the first specific federally-funded health care system for Native Americans.

This was expanded upon in 1955, with the creation of the IHS.

Further legislation in the 1970s bolstered the IHS to ensure it would become a truly unique branch in the American healthcare system, providing absolutely free health care to Native Americans, regardless of what they can pay.

Over the coming decades, robust community health schemes, and increased access to physicians, in a clinic-driven model eventually similar to that of the Veterans Administration (VA), saw health metrics increase across the board.

Recent IHS strategies around clinical care have considerably reduced diabetes rates amongst Native Americans, which towered above other groups.

Though limited resources have led many to use private providers today, the IHS says that around half of all Native Americans receive health insurance through the agency (around 14.9 percent are without any health insurance, three times the rate of white Americans).

“One of the few bright spots to emerge from the history of relations between American Indians and the federal government is the remarkable record of the IHS,” Abraham Bergmen, David Grossman, Angela Erdich, John Todd and Ralph Forqeura wrote in a political history of the agency, in 1999.

“The gains occurred in spite of chronically low funding and can be attributed to the combination of vision, stubbornness, and political savvy of the agency’s physician directors and the support of a handful of tribal leaders and powerful allies in the Congress and the White House.”

Continuing disparities

Despite the gains, the disparities remain wide. Beyond the impact of COVID-19, Native Americans still die at higher rates than their fellow citizens in liver disease, chronic respiratory disease, and tuberculosis, amongst other illnesses.

Native Americans and Alaska Natives born today are expected to live to 73, five and a half years less than the U.S. ‘all races’ population. In Montana, the life expectancy of native American males is only 56.

Given the higher health status enjoyed by most Americans, the lingering health disparities of American Indians and Alaskan Natives are troubling.

Though it is worth noting the Trump administration proposed an increased budget of $5.9 billion last year, the IHS still struggles with clear underfunding.

In 2017, NPR reported that the previous year’s IHS budget of $4.8 billion meant that the federal prison system saw more than four times spent on each prisoner, than native Americans had spent on their health care. A vacancy rate of IHS physicians may be up between 20 and 25 percent.

Additional studies have shown that around a quarter of Native Americans experience discrimination when going to a doctor, or medical clinic, too.

“Given the higher health status enjoyed by most Americans, the lingering health disparities of American Indians and Alaskan Native are troubling,” the IHS itself writes, on present-day Native American health.

“In trying to account for the disparities, health care experts, policymakers, and tribal leaders are looking at many factors that impact upon the health of Indian people, including the adequacy of funding for the Indian health care delivery system.”

“The American Indian,” Johnson said, in 1968, “once proud and free, is torn now between white and tribal values, between the politics and language of the white man and his own historic culture.

“His problems, sharpened by years of defeat and exploitation, neglect and inadequate effort, will take many years to overcome.”

From a health care perspective, many years still remain.