Viewed through the prism of history, those living in North America in the 1770s lived through a time of great change.

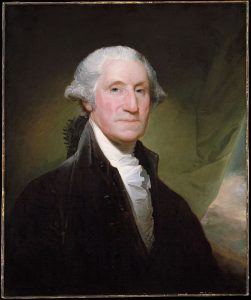

A nation was born, and working hard to shelter its small flame of independence. George Washington’s armies fought against the British, with victory ultimately wrestled by 1783.

For those who lived through it, the Revolutionary Period was an era like ours—defined by a society-wide outbreak of disease. Between 1775 and 1782, it is understood more than 130,000 North Americans died, in what would be the last continent-wide smallpox epidemic.

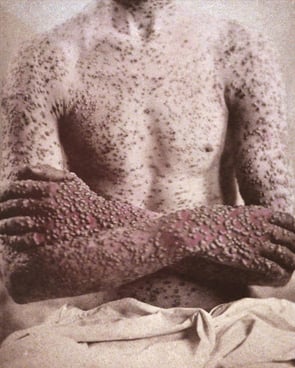

Since first European contact, smallpox regularly swept through the New World. Killing nearly a third of those infected by it, it destroyed entire cultures and ways of life. Just before the Declaration of Independence was signed, it re-emerged for the birth of the United States of America.

While the American Revolution may have defined the era for history, epidemic smallpox nevertheless defined it for many of the Americans who lived and died in that time.

“While the American Revolution may have defined the era for history,” the New Yorker wrote, in 2001, “epidemic smallpox nevertheless defined it for many of the Americans who lived and died in that time.”

Smallpox would bring the young nation to its knees, but also saw its great hero—Washington—confront the disease like none before him.

Armed with managed isolation and a ‘proto-vaccine’, Washington’s priority might have been the health of his army.

But the future first President achieved more than that, embarking upon an impressive campaign of large-scale disease immunology nearly two decades before the first smallpox vaccine was even developed.

“George Washington’s embrace of science-based medical treatments—despite stiff opposition from the Continental Congress—prevented a potentially disastrous defeat, and made him the country’s first public health advocate,” Andrew Lawler wrote for National Geographic about Washington’s smallpox response, in April.

The impact of smallpox

Washington knew firsthand how bad smallpox, which would result from the variola virus, could get, having been infected as a teenager.

When he was 19, Washington and his older half-brother travelled to Barbados in 1751, in hopes the warm sea air would help cure his sibling’s tuberculosis (it wouldn’t; Lawrence Washington would die the following year).

A day after they arrived, the brothers dined with a prominent local merchant, whose family members were suffering from smallpox.

Like COVID-19, smallpox has an incubation period of up to two weeks, meaning infected would often spread it. Within a fortnight, the future President had the disease.

Though suffering a mild case, it is thought Washington was “bedridden for weeks, rocked by high fevers and chills, severe body aches, a twisted stomach and the telltale oozing rash.”

Smallpox is thought to have been brought to North America by British and German troops sent to fight in the Revolutionary War in the mid-1770s.

Over six years, at least five times more were killed by the disease than actual fighting, with a mortality rate of up to 30 percent. For the last week of July, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported the combined mortality rate of pneumonia, influenza, and COVID-19 to be 7.8 percent.

Now impossible to measure, the impact on Native Americans was particularly hard. Indigenous groups along on the West Coast suffered greatly, with around one in three in the Pacific Northwest dying from it.

A compelling case can be made that his swift response to the smallpox epidemic and to a policy of inoculation was the most important strategic decision of [Washington’s] military career.

“As smallpox squeezed the life from thousands of victims,” Elizabeth Fenn, a history professor and author of Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-1782, wrote, “it extinguished the accumulated wisdom of generations, leaving those who survived without the familiar markers by which they organized their worlds and leaving the generations that followed with a mere shell of their former heritage.”

The quarantine approach

With most British exposed to smallpox as children, their immunity was high compared to their continental cousins. For example: only 23 percent of North Carolina enlistees in Washington’s army, in 1777, had ever had smallpox.

“It comes down to herd immunity,” Fenn told History.com. “You either have to let people be exposed to the disease and naturally acquire immunity, which could be devastating for this troops and having devastating consequences for the war.

“Or somehow quarantine your troops, which means they’re not going to be able to fight. Or immunize them.”

Smallpox first broke out among both the Continental and British forces during the Siege of Boston in late 1775 (there have been suggestions the British purposefully sent infected civilians and soldiers into American lines).

An American army laying siege to Quebec was also riddled with the disease. Eventually, a third of the 10,000 strong force would die of smallpox—including its commander, John Thomas, a Massachusetts doctor—and it would be forced to retreat.

“The smallpox is ten times more terrible than Britons, Canadians, and Indians together,” John Adams, a Founding Father who’d become the second U.S. President, wrote, in 1776.

With the Continental Army easily outnumbered by its opponents, Washington understood the importance of managing disease within his forces. Following the capture of Boston, he began a managed isolated approach to the disease.

He set up his camp across the Charles River from Boston, and forbade any contact between civilians and soldiers. Military cases were sent to a quarantine hospital near Cambridge, Massachusetts, while civilians were held in Brookline.

Only recovered soldiers were allowed to venture into Boston, itself.

Washington’s proto-vaccine

With the need for movement to match the British, and new recruits joining his army, Washington’s quarantine approach needed adapting.

He turned to variolation. Initiated in Asia centuries before, the rationale was to infect people with a milder dose of smallpox to build immunity. Originally, it is thought that dried smallpox scabs were blown up the nose.

By the time the concept reached Europe in the early 1700s, variolation had effectively been transformed into a proto-vaccine. Between 2 and 10 percent of those who received would still die of smallpox.

“An inoculation doctor would cut an incision in the flesh of the person being inoculated and implant a thread laced with live pustular matter into the wound,” Fenn told History.com.

“The hope and intent was for the person to come down with smallpox. When smallpox was conveyed in that fashion, it was usually a milder case than it was when it was contracted in the natural way.”

Outlawed in many of the early states, including Washington’s Virginia, variolation was wildly controversial, and unsupported by the Continental Congress.

A compelling case can be made that his swift response to the smallpox epidemic and to a policy of inoculation was the most important strategic decision of [Washington’s] military career.

Martha Washington received one in June 1776, and, following the counsel of Dr. William Shippen (a Philadelphia physician who helped set up the first American med school), her husband convinced Congress to adopt the practice for its army the next year.

“The small pox has made such Head in every Quarter that I find it impossible to keep it from spreading thro’ the whole Army in the natural way,” Washington wrote to fellow revolutionary leader John Hannock.

“I have therefore determined, not only to inoculate all the Troops now here, that have not had it, but shall order [Dr.] Shippen to inoculate the Recruits as fast as they come in to Philadelphia.”

Fully funded by Congress, the army’s inoculation programme was carried out in complete secret from the British. With recovery taking up to a month, Washington didn’t want to give his opponents the drop on when he’d be most short-handed.

Washington’s legacy

By the end of 1777, up to 40,000 soldiers had received inoculations, and stayed healthy enough to eventually defeat the British. England’s Edward Jenner completed the world’s first ever vaccination, against smallpox, in 1796.

“A compelling case can be made that his swift response to the smallpox epidemic and to a policy of inoculation was the most important strategic decision of [Washington’s] military career,” historian Joseph Ellis told History.com.

Though smaller outbreaks occurred in the 1830s, 1840s, 1860s, and early 1900s, no disease impacted North America like smallpox again until the Spanish influenza.

While smallpox itself was fully eradicated by the late 1970s, Washington’s immunological impact on the U.S. armed forces continues today.

The U.S. Army continued to vaccinate recruits against smallpox until the early 1990s, two decades after it had ended amongst the civilian population.

After 2003, only those about to be deployed to ‘high risk’ regions would receive a smallpox vaccination, along with those for anthrax, typhoid, and others (when they sign up, present-day military recruits can receive up to 18 separate vaccinations).