Located on the state border with southern New Mexico, Loving County lies deep in the kind of West Texas Cormac McCarthy might dream about.

The land is open and cinematic, but dry and hard to live off. Folks work cattle, or oil. There’s only one two-story building, and it’s the county courthouse.

Though constantly bolstered by hundreds of out-of-county oil workers, Loving is understood to have less than 170 permanent residents. Mentone, the only town, has 19 of them.

For decades, its claim to fame was being the first county in Texas to appoint a female sheriff, Edna Reed Clayton DeWees, in 1945.

Surrounded by a veritable land sea, Loving has stood like the Alamo again during the Covid-19 pandemic – until this week.

The [Covid-19] crisis is really widening the fractures that have already existed in rural communities.

On Tuesday, the New York Times reported at least one county resident was Covid-19 positive, making it the last in the continental United States to record a case. A former long-time Moloka’i Island leper colony, Hawaii’s 86-person Kalawao County is now the last Covid-free patch of the U.S.

In a deeply-reported, on-site feature for the Times, J. David Goodman portrayed Loving as a tough, hard-working community with a small, sheet metal health clinic for those who fall ill. Though unreported, it is thought that coronavirus had already popped up before this week, at the large rig worker camp in Mentone.

“To say that we’re the only place in the United States that’s never had a Covid case, I don’t think that’s true,” Steve Simonsen, the county attorney, said. “It’s a nice little bit of hype, but certainly it’s been here.”

As massive as the U.S. is geographically, and as isolated as its most isolated communities chose to be, the Covid-19 pandemic is now truly a continent-wide public health experience for Americans.

More than any other moment in it, rural folks, like those in Loving, are now starting to feel it the hardest. Today—ironically—is National Rural Health Day.

“The [Covid-19] crisis is really widening the fractures that have already existed in rural communities,” Brock Slabach, senior vice president at the National Rural Health Association (NRHA), told NPR last month.

Pre-existing conditions

Population-wise, rural America is defined as everyone who lives outside urban clusters of 2,500 or more. Urban America is characterized as centers of more than 50,000.

During the last U.S. census in 2010, it was determined that 19.3 percent—or around 60 million people—of Americans, lived rurally. In 1910, 54.4 percent did.

The challenges of providing adequate medical care for these communities have been known for generations, and remain the same: too many patients for too few physicians, a constant lack of resources and medical facilities, patchy specialized knowledge, and a communication network not fully equipped to deal with potential new solutions.

With waves of hospitals closing—especially in Texas, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Georgia, Alabama, and Missouri—over the last decade, ‘medical deserts’ have been opened up across the country.

Shortages of rural physicians have been notable for decades. The ones that remain have increasingly less resources to deal with a population with increasingly more health issues.

“Generally, people who live in rural America are sicker, older, and come from a lower socioeconomic level,” Dr. David Schmitz, a past president of the NRHA, told Medical Economics last year.

“They are less well insured and tend to suffer from a lot of chronic disease. And, by nature of where they are, it’s often difficult for them to access healthcare, even basic primary care.”

Add in the reality of nationwide racial health disparities being even more out-sized in rural areas, and you have a powderkeg a pandemic could easily ignite – and has.

With the vast number of healthcare systems in less-populated states, especially across the Midwest, really feeling the pandemic strain, it is worth noting the increasing rate of closure of rural hospitals in many of those states over the last two decades.

These rural hospitals are designed for primary care [or] general surgery. They were never designed for a global pandemic response.

Pew Trusts say 163 hospitals have closed in rural regions since 2005, with around 120 of those coming in the last decade. According to research by the Rural Health Research Program at UNC-Chapel Hill, the 19 that closed in 2019 set the record for the most in a year.

Though 1844 rural hospitals are still in operation around the U.S, Forbes shows around a quarter were at risk of closure, pre-pandemic. In addition to the bigger facilities, nearly one in ten rural health clinics closed between 2012 and 2018.

“These rural hospitals are designed for primary care [or] general surgery,” Alan Morgan, chief executive of the NRHA, told USA Today. “They were never designed for a global pandemic response.”

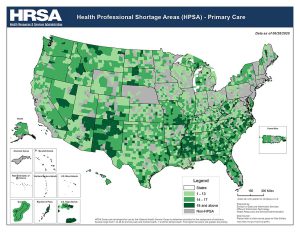

The increasing shortage of facilities is only matched by the continuous shortage of rural-based physicians. National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM) data shows rural areas have only 13 physicians per 100,000 people, compared to 33 in urban areas.

There are only five primary care providers per 100,000 in rural areas, compared to built-up ones, while clear shortages exist for dentists, obstetricians, and gynecologists are also obvious.

With more than 25 percent of rural primary care providers aged 60 or more, the challenge of incentivizing young doctors to replace them is obvious.

“It is an unsustainable situation,” Ann Peton, director of the National Center for Rural Health Works, told Pew Trusts.

Covid-19 hits rural America

Though more isolated from the first and second nationwide Covid-19 spikes, early August bought that tide that had worried experts from the very beginning of the pandemic.

According to the most recent USAFacts statistics, 1,691,737 positive Covid-19 cases have been recorded in rural America, representing 15.09 percent of total cases. 30,227 rural Americans have died because of coronavirus, around 12.33% of the total U.S numbers.

The rural figures are comparable to nationwide Covid-19 outbreaks in the likes of Colombia, or Peru. If they were nations themselves, North and South Dakota would have the worst, and third worst, Covid-19 mortality rates in the world, respectively.

Inconsistent, politically-charged public messaging about masks and social distancing, —neither of which have ever been fully embraced by rural Americans—have almost certainly contributed to the recent spike. Conservative, rural states like South Dakota, Nebraska, Idaho, Wyoming, and Iowa are amongst the few who still don’t have a mask mandate.

With Thanksgiving and Christmas still to come, rural Covid-19 case numbers and deaths from mid-December through January have the potential to become truly shocking.

“Nearly half of all rural counties are considered red zones – that is, they are experiencing a higher rate of new infections,” Olugbenga Ajilore, a senior economist at the Center for American Progress, recently wrote.

“While any level of new Covid-19 infections is unwanted, this level is untenable for any community if it is to sustain a vibrant and healthy economy.”

It’s exhausting to think maybe we’re only halfway through this. Maybe we have another six months or eight months of this roller coaster.

Big Horn County, Montana is one of those red zone areas. With 1700 total positive cases, one in eight people have been infected. 47 have died. With a Crow Reservation making up the majority of the county’s total populations, Big Horn also highlights the racial disparities that lie within rural America’s Covid-19 plight.

Native Americans, who are more likely to live rurally, are more than five times as likely as non-Hispanic white Americans to be hospitalized due to Covid-19, with the Navajo Nation suffering especially hard this year. According to a recent Syracuse study, rates of rural Covid-19 mortality are highest amongst Black and Hispanic Americans.

“I feel as though tribal nations have an effective death sentence when the scale of this pandemic, if it continues to grow, exceeds the public resources available,” Fawn Sharp, the President of the Quinault Indian Nation, told the New York Times, in July.

Remedies, and realities

In late March, the Federal government’s early pandemic stimulus bill provided much needed resources to rural healthcare, including extra provisions for the Indian Health Service.

Yet with another government injection of funding uncertain, at least until President-elect Joe Biden takes office, it appears the short-term issues in rural health look unlikely to be solved.

Indeed, while the recent announcement of the success of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines represents the first rays of sunlight from a post-pandemic world, distribution issues virtually ensure rural communities will receive it after most others. Pfizer’s potential vaccine requires storage at -70 C (-94 F), a capacity many rural medical facilities lack.

In the medium term, the expansion of Medicaid in more states should have a positive impact on rural health. Several low-population conservative states have recently signed on, with more potentially on the cusp.

With patients trained to use telemedicine, an improvement of the rural broadband network would lighten the load on overworked rural physicians (around a quarter of rural Americans deal with poor internet speed). More scholarships assisting med students from rural areas return home to help their communities seem urgent, and necessary.

Pennsylvania is attempting a “bold” new rural health initiative which guarantees the amount of revenue participating hospitals receive in a year, freeing them up to focus on preventative care, and chronic illness treatment. Known as the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, its success could potentially be replicated elsewhere in the U.S.

Despite the potential ways forward, Covid-19 will continue to consume America’s rural healthcare well into 2021. For West Texas oil workers and cowboys, to Native Americans in rural Montana, the pandemic’s lasso is a long way from loosening.

“It’s exhausting to think maybe we’re only halfway through this,” Big Horn County mayor Purcell Joe told Bloomberg.

“Maybe we have another six months or eight months of this roller coaster. When you don’t see an end in sight, it’s very hard to keep your staff motivated.”