In late 1968, NASA astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders were preparing to be the first humans to leave Earth orbit, headed for the Moon.

Before the trio were to create history, they—like millions of others around the world were going to—had to sit down, and receive a vaccination in the middle of a pandemic.

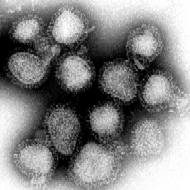

Caused by the H3N2 strain of the influenza A virus, the 1968 ‘Hong Kong Flu’ was a global outbreak that may have caused the deaths of up to four million, worldwide.

Although the estimated morbidity and mortality of [the 1968] pandemic was only a small fraction of … the 1918 N1N1 pandemic, the ongoing impact of influenza A(H3N2) virus on public health has been profound.

First recorded in Hong Kong that July, the bird-related flu was widespread in the United States by the time Borman, Lovell, and Anders took their shots.

Germany and Japan were amongst the countries worst hit by the H3N2 strain, which the New York Times described as “one of the worst in [United States] history.”

With commercial air travel beginning to touch every corner of the globe, the 1968 pandemic was likely the world’s first globally spread by the scientific achievement of flight.

Though differing wildly from today’s global coronavirus pandemic—both in terms of deaths and societal impact—similarities between certainly show the enduring impact that short memories have over lessons learnt.

“Although the estimated morbidity and mortality of this pandemic was only a small fraction of that associated with the 1918 N1N1 pandemic, the ongoing impact of influenza A(H3N2) virus on public health has been profound,” Dr. Barbara Lester, Dr. Timothy Uyeki, and Dr. Daniel Jernigan, wrote in the American Journal of Public Health, this May.

The pandemic’s early cousin

The ‘Hong Kong Flu’ story begins more than a decade before, during an often forgotten bird flu outbreak in 1957.

The first cases of the H2N2 viral outbreak that year began to appear in the southwestern Chinese province of Guizhou, in February Two months later, the Times reported up to a quarter of million people in Hong Kong were receiving treatment for the virus.

By July, more than a million Indians had contracted it. More than a million lives are understood to have been claimed by the pandemic, by 1959.

Some who caught the virus had little more than a cough or mild fever, though further complications could include pneumonia, bronchitis, and further cardiovascular diseases.

Initially thought a recurrence of the devastating 1918-1920 Spanish influenza, legendary American virologist Dr. Maurice Hilleman discovered that it was actually a whole new strain of flu after comparing a sample from a young U.S. Naval service member who had picked it up in Hong Kong, to previous ones.

“What he found was that there was this dramatic shift,” Dr. Paul A. Offit, a prominent American vaccine expert, told History.com, in May.

“Both those proteins were completely different from what they had been previously. They hadn’t just drifted, they’d shifted.”

Despite initial challenges, virologists were quickly able to create an effective vaccine. Limited numbers of Americans received one, by late 1958.

Beyond eventual distribution of the vaccine itself, widespread public health measures included the closure of schools in Ireland, and government-recommended self-quarantining in the U.K.

British scientists showed the 1957 strain, which was known colloquially as the ‘Asian flu’, caused complications in only three percent of cases, with a 0.3 death rate.

While the eventual rate of complications for COVID-19 is yet to be known, research from John Hopkins University shows the coronavirus mortality rate in the United States to be ten times that of the British number, in 1957. In Mexico, the COVID-19 mortality rate is 10.6 percent of recorded cases.

A spreading outbreak

Like all countries, Hong Kong experiences the ebb and flow of flu seasons, with the worst periods coming between January and April, and July and August.

…our present habit of forgetting and looking in the other direction would seem a catastrophic act of global folly.

By early July, in 1968, Hong Kong public health officials were discovering an overabundance of patients with flu-like symptoms, and worse. By the end of the month, 500,000 are understood to have been infected.

Though still relatively new, commercial international air travel saw the virus spread at a fast rate, globally.

Indeed: the first ‘Hong Kong Flu’ case in the U.S. was a young Marine who’d recently flown home from the Vietnam War. Just before he left, he’d been sharing a bunker with a friend who had just visited Hong Kong.

Rapid contact tracing from the Marines quickly established, and isolated, a large number of those potentially infected, but the virulence of the new flu strain forced the American government to work fast.

Within a week of the first case, the CDC’s predecessor, the National Communicable Disease Center, began communication with state officials about the new H3N2 strain.

By then, cases were popping up in other West Coast cities, as the virus spread amongst the American population. Amongst others, a scout jamboree in Pennsylvania served as a ‘super-spreader’ event.

A second peak in late 1969 and early 1970 was more severe than the first, experienced that winter.

Response, and impact

The new virus—created by an antigenic shift, essentially a reassortment of H2N2 genes—was quickly isolated by Hong Kong researchers. Spearheaded by the U.S and U.K, a worldwide effort saw a highly effective vaccine being manufactured as early as November.

15 million global doses were available by the pandemic’s early peak, in January 1969. Powerful new antivirals were used to fight the virus, too.

The 1968 ‘Hong Kong flu’ had only a 0.5 percent mortality rate. Alarmingly, those younger than 65 died of flu or pneumonia complications, during the brief pandemic.

Beyond isolated school closures and increased screening at some airports, there were little widespread societal changes due to the flu pandemic.

Racial animus towards Asians was stirred by it across the United States and Europe, however, with some tabloids calling the ‘Mao flu.’ The sentiment echoes today, with President Donald Trump’s labelling of COVID-19 as “the Chinese virus.”

Though more than 100,000 are thought to have died in the 1968 pandemic in the United States, and 30,000 in the U.K, the seasonally-regular impact of the flu makes the numbers hard to measure against those experienced during today’s COVID-19 crisis.

“The number of deaths caused by that pandemic in the first two years, 1968 and 1969, weren’t much higher than the average seasonal flu,” Dr. David Morens, a senior scientific adviser at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told Snopes in May.

COVID-19 is far more deadly than the 1968 pandemic virus … we have about five percent of herd immunity right now in the nation.

“So, it really was kind of a pandemic that was such a wimpy pandemic it didn’t make much of a blip on the radar screen.”

“COVID-19 is far more deadly than the 1968 pandemic virus … we have about five percent of herd immunity right now in the nation,” Morens later continued.

“By the time we get to 70 percent, think about that, that’s 14 times as many cases as we have now. And if you project that onto 80,000 deaths you can see [if we just] let things go, as we did in the Woodstock era, we’d have more than one million deaths.”

Lessons learnt

Though the ultimate form of isolation from a virus, the H3N2 flu strain didn’t accompany the crew of Apollo 8 to the Moon, in 1968. The three astronauts returned to Earth as parade-worthy heroes.

Despite smaller recent coronavirus outbreaks like SARS (2004 to 2006), the world has been shielded against the society-changing impacts of a pandemic felt by earlier generations since, too.

Though the Spanish influenza was still relatively fresh in medical researchers’ minds, most who lived through the late 1950s and late 1960s were unscathed by their era’s twin pandemics.

Recent outbreaks by SARS and other diseases didn’t prepare global society for the current COVID-19 pandemic.

“[More than 11,000 people died in west Africa from an Ebola outbreak in 2014,” Martin Kettle wrote, in a 2018 Guardian column reflecting on the century following the Spanish influenza.

“And imagine if Ebola manages one day to become airborne, as [the] flu did. If something like that happened in the modern world, we would quickly find we were living in a fools’ paradise.

“And our present habit of forgetting and looking in the other direction would seem a catastrophic act of global folly.”