Sometimes it is hard to know whether time anchors you to a place, or whether it’s the other way around.

Six years ago, Chris McNeil was working as a pre-med volunteer at Oklahoma State University Medical Center in Tulsa when he found out that he passed his MCAT.

This month, McNeil, the first recipient of OnlineMedEd’s Scholarship for Future Black Physicians, began his medical residency at the same hospital.

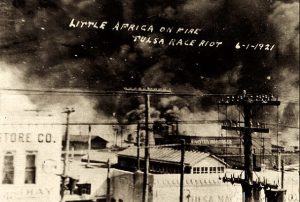

On Monday, the city will recognize 100 years since one of the worst acts of mass racial violence in American history occurred. On May 31, 1921, a white mob burned Tulsa’s Greenwood District—known to history as ‘Black Wall Street’—to the ground, killing 300 Black residents. More than 1250 homes, businesses, and a hospital were destroyed.

I always remember what my Dad told me: you never set up camp in the peaks or the valleys.

On Wednesday, McNeil will turn 32. As part of his scholarship-winning application video, he walked the same streets that had been reduced to rubble a century before, speaking of the challenge that lies ahead of a new generation to build, succeed, and bring others with them.

McNeil, who studied osteopathic medicine at OSU Center for Health Sciences, is thought to be just the third Black emergency medicine resident at OSU Medical Center. Dr. Yakiji Bailey was its first Black chief resident.

“Everyone’s so inclusive, it’s a place I love and those people are family, but it’s important information to know,” he says.

“I don’t want to stay the third [person]. By the time I’m in Dr. Bailey’s position, I want the 103rd to have come through. Going about that, it’s important to know the history.”

‘Offense and defense’

Though he admits he is not an ‘adrenaline junkie’ like many who head into emergency medicine, McNeil says he was attracted to the discipline due to his ability to meet a range of patients, with a range of issues.

“You’re kind of the first line of offense and defense for the hospital,” McNeil, a former OSU wrestling star who grew up in Lawton, Oklahoma, says.

“[It’s] a specialty where you are mastering the unknown and essentially learning how to control chaos as part of your job. I like those aspects, and as I want to be involved in my community, all that stuff interplays in emergency medicine.”

Beyond the obvious, immense support of his family—located in Tulsa, Lawton, and Dallas— McNeil is grateful to count Dr. Bailey as a mentor. During McNeil’s rotations at OSU Medical Center, the pair got to know each other, with the older physician offering the ‘rookie’ guidance.

“When you’re the only Black person in a certain vicinity, you automatically become the diversity expert by default,” he says.

You’re kind of the first line of offense and defense for the hospital. [Emergency medicine] is a specialty where you are mastering the unknown and essentially learning how to control chaos as part of your job.

“[I] sought out Dr. Bailey, because there were things I could talk to him about that I didn’t have to explain, they just come out naturally in conversation. At the same time, he’s thinking about what family is to me, what are my ambitions, what do I want to do in emergency medicine, [and] knowing that being a resident and doctor isn’t the be-all and end-all.”

The most recent U.S. government statistics show just 2.9 percent of all American med students are Black men, meaning McNeil would often find himself playing the role of the ‘diversity expert’ at med school. Academic medicine sometimes refers to those in McNeil’s position as paying a ‘minority tax.’

As he told me last November, McNeil is happy to have the conversations and wants those politely asking questions to understand how difficult they can be.

While the murder of George Floyd remains fresh in the memory for current Black med students and residents, the heartbreaking recent congressional testimony of three of the few remaining Tulsa massacre survivors shows older ones are just as raw. Viola Fletcher, the eldest who spoke, was 107.

“Whether you’re watching movies, or it’s Martin Luther King Day, or you’re just learning about history, [you find that] what’s going on today is not new,” McNeil says.

“There’s more technology and it’s easier to talk, but the ideas people had and the things that are happening in society, they’re not new. At the height of the Civil Rights movement, similar conversations were going on. If you look at it that way, it’s kind of scary because not that much has changed.

“At the same time, when you look at what we can do, all the potential is still there to have some dynamic changes. The way I look at that the most are how many conversations a day can I have where people feel comfortable talking to me about things.

“If it’s in the ER, great. If it’s in the public school setting, excellent. If it’s part of a board meeting, and people are having that sense of ‘huh, I never thought of it that way,’ that’s great.

“That’s the least I can do, so that way, when my children get out there, they can look back in history and know that things have at least moved a little more forward. Just one percent is all I’m asking for.”

‘The peaks and the valleys’

The months before McNeil’s residency started provided him with a medical education of a modern-day kind. As a med student volunteer, McNeil was amongst the first to receive a Covid vaccination in Tulsa.

On social media, he noticed a great deal of misinformation about Covid vaccinations. Within the Black community, apprehension about them was just as prominent – and understandable. As a young Black doctor, McNeil knew how important it was to encourage others to get their jabs, and sought about being an advocate on his social media channels.

“We can’t solve all the disparities in one Facebook or social media post, but we can start curtailing some of the news and saying ‘hey, these things are inherently good,” he says.

“When you can see people in your community doing it, it’s a lot easier to start having those conversations.”

Like most American minorities, the Covid pandemic has been terrible for Black Americans. According to recent CDC data, Black Americans are three times more likely to be hospitalized from a Covid infection than white Americans, and nearly twice as likely to die from it.

“People were so confused about how Covid was [seemingly] indiscriminately targeting marginalized populations,” McNeil says. “It was so funny that, after going from conversation to conversation, there wasn’t a Godzilla, an asteroid that was coming – or an Armageddon.

“It was the same basic problem being reiterated around lack of access, lack of understanding, lack of infrastructure, timing discrepancies, comorbidities – all these things that built Covid up into a superbug because what it did was expose infrastructure deficits existing in communities that are marginalized.”

Despite the challenges, McNeil—the son of a United States Army physician’s associate—remains as driven as ever to be a great doctor. Though residency brings another milestone to celebrate, don’t expect a change in commitment any time soon.

“I always remember what my Dad told me: you never set up camp in the peaks or the valleys,” he says. “Not that you can’t enjoy the moment, but you’ve always got to be cognizant of the road to come.”

“I can’t afford to be a terrible resident, I can’t afford to not turn up to work, I can’t afford to have an off day. That weight to me is fuel because, at the end of the day, my excellence feeds my kids and my family, and it sets the standard for other people to come.”

Time flies over us

Celebrated American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne once wrote that time flies over us, but leaves its shadow behind. The shadow of the Tulsa Massacre is one of his nation’s darkest.

In 1921, planes allegedly to dropped handmade bombs on Greenwood. Black bodies were reported to have been thrown in the Arkansas River, while mass graves were also dug. More than 10,000 were made homeless, with some later forced to labor without pay.

“Greenwood, where Black success embodied the American dream, was no more, suddenly, dreadfully wiped out,” the New York Times reported, in an impressive digital feature this week that re-created the look, feel, optimism, and eventual loss of what Greenwood had become, pre-1921.

We can’t change what happened in the past, but we can … take the information to build for the next renaissance.

Despite its three lead plaintiffs all speaking for Congress, the lawsuit against Oklahoma and Tulsa arguing it’s responsible for the violence and destruction of Greenwood remains pending.

As of today, not one person has ever been prosecuted or punished for their role in the Tulsa Massacre. The shadow of time is one thing. Justice is very often another.

Today, McNeil will spend the day speaking to Black Tulsa residents about vaccine hesitancy. He’ll spend Monday with his family and reflect on the massacre in his own way—late cancellations have meant most of the major commemoratory events won’t be held—but he wants people to know that, after 1921, the Greenwood community was rebuilt. That good can come from bad.

“We can’t change what happened in the past,” McNeil says, “but we can … take the information to build for the next renaissance.”