On April 17, 2018, the statue of J. Marion Sims was pulled down for a second time in New York City.

Split between Bryant and Central Park, the father of modern gynecology towered over the heads of New Yorkers for over 120 years. There was a hood over his own when the truck finally pulled away. A crowd surrounded it and cheered.

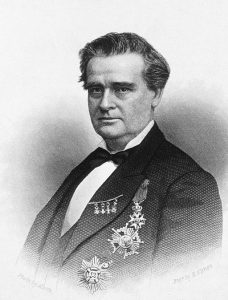

It is difficult to think of a figure whose racist worldview, unethical practices, and genuine contribution to medical understanding creates a more complicated paradox than that of James Marion Sims.

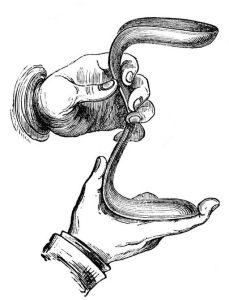

As a doctor in antebellum Alabama, Sims transformed women’s health with the invention of the speculum and treatment of vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) in 1849. Today’s gynecologists still use his instrument and treatment position as core elements of their practice.

Sims’s use of the speculum and his teaching of the fistula procedure in Europe helped spark further study of gynecology across the Atlantic. Most importantly, he cured a common, painful condition that saw women socially segregated for thousands of years.

Many other elements of the Sims story are more difficult to stomach. His ground-breaking surgeries were more akin to medical experiments that took place on three female slaves—Anachara, Lucy and Betsey—without consent or anesthetic.

There is no way to honor Sims as a hero, while properly acknowledging those who suffered under his surgeon’s knife, so that others could someday be healed with less pain and more care.

Born into a wealthy rural South Carolina family, Sims owned 17 Black slaves during his life including a couple given to him as a wedding gift from his in-laws. He viewed Blacks to be less intelligent than whites and considered their pain threshold to be higher.

An avowed Confederate who performed a successful fistula treatment on the last Empress of the French, Sims’ influence nearly nudged a major international power into the American Civil War on the side of the South. Ever since his death in 1883, defenders and critics have waged war over his legacy, creating more confusion.

Yes, the statue has come down, but the swirling portrait of Sims still remains along with an enduring question: what—if any—unethical or immoral practice is acceptable if genuine medical progress results from it?

“There is no way to honor Sims as a hero,” Adam Serwer wrote for The Atlantic, in April 2018, “while properly acknowledging those who suffered under his surgeon’s knife, so that others could someday be healed with less pain and more care.”

A plantation physician

Technological and social restrictions made the 1840s a difficult time to be an American doctor. Medical education was still being formalized, much less standardized. The profession was exclusively made up of privileged white males.

New procedures were often learned by book or journal. Physicians who made important medical breakthroughs became celebrities, with accolades and influence often following.

However, some of history’s most groundbreaking medical procedures were occurring in the South before the Civil War. In 1809, Kentucky’s Dr. Ephraim McDowell conducted the first successful abdominal surgery, removing a 22-pound ovarian tumor from Danville’s Jane Crawford.

In 1842, Georgia’s Dr. Crawford Long removed a tumor from the neck of James Vernable. Using sulfuric acid, Long, an early graduate of America’s first medical school, was one of the first Western doctors to use a successful anesthetic during surgery.

Sims was born on January 25, 1813, in Lancaster County in rural South Carolina. After a brief medical course in Charleston, he moved to Philadelphia where he finished his studies at Jefferson Medical College in 1835. The ambitious young doctor began his practice in Mount Meigs, Alabama, before moving to Montgomery in 1840.

As well as treating whites and freed Blacks at his popular practice, Sims also practiced on slaves, gaining a reputation as a ‘plantation physician.’ An owner of many slaves himself, his view on Black Americans was well-known.

He also had little interest in caring for female patients. The father of modern gynecology admitted to initially refusing all female patients and generally “hated … investigating the organs of the female pelvis.”

At the time, gynecology was a vastly under-resourced and under-taught medical field. Examining female reproductive organs was considered repugnant by many doctors, who were almost exclusively male. Most didn’t see their first clinical cases in women until they began to practice and found “little room to see [vaginal wounds] … let alone to stitch sutures in the secreting tissue.”

According to author J.C. Hallman—whose exhaustive research deserves rich recognition for its wider illumination of the Sims story—things changed in 1845 when he was called on to treat a white woman who fell off a horse.

Suffering a ‘dislocated uterus’, Sims was able to help ‘re-inflate’ her vagina using a combination of her body’s side-on position and his fingers creating pressure against her perineum and rear vaginal wall. His success made him think of three females slaves who were being kept at a ‘negro hospital’ behind his Birmingham clinic.

Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey

Usually caused by prolonged labor, a VVF was essentially a tear into the bladder from the vagina. Its evidence has been found on a female Egyptian mummy and recorded by early Persian doctors.

For women who suffered from it, a VVF tear was an agonizing experience. Unable to control urination due to the open wound, they suffered in near-constant pain as urine spilled out onto it. Its smell was continuous.

Women with a VVF would often become social outcasts, castigated by society. The mental toll of it all is hard to imagine. Accurately estimating what portion of women suffered from it is just as difficult.

“Women who experience obstetric fistula suffer constant incontinence, shame, social segregation, and health problems,” the World Health Health Organization wrote in 2018. Though now quickly treated throughout most of the world, the WHO says more than two million still live with untreated fistula in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

On plantations near Montgomery, Alabama, Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey were suffering from it in 1845. Little has been recorded and remembered of their lives, beyond the knowledge that all three endured from long, difficult childbirths. Halleman wrote that Anarcha was in labor for three days before Sims saw her.

Medical care was basic for slaves, but Hallman wrote that “tending to the medical needs of current and former slaves was an economic necessity in an area where two-thirds of the population [were] Black.”

Inspired by what he had learned from his white patient, Sims bought a pewter spoon to act as his initial tool to keep the slaves’ vagina open. What followed lacked medical consent from the three women—by law, not required by slaves at the time—nor the use of an anesthetic.

Though newly available, effective anesthetics were hard to come by and risky to use in 1845. Early on—incredibly—Sims didn’t consider a fistula operation to cause enough pain to use it. Stripping away a final level of dignity, it is also understood Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey were forced to undergo the experimentation fully naked.

“Two medical students assisted him with the woman—her name was either Lucy or Betsey, depending on how you read Sims’s account—and as soon as they put her in the knee-chest position and pulled open her buttocks, her vagina began to dilate with a puffing sound,” Hallman wrote.

“Sims sat down behind her, bent the spoon, and turned it around to insert it, handle first. He elevated her perineum and looked inside. He could see the fistula as plainly as a hole in a sheet of paper.”

“I saw everything as no man had ever seen before,” Sims later recounted, in his memoirs.

Until ultrasound became prevalent over the last 20 years, using the speculum was the only way a gynecologist could inspect female reproductive organs or perform any sort of internal gynecologic surgery.

Despite the success of his proto-speculum, successful treatment of the fistula didn’t come right away. Tools were improved and adapted as did Sims’ techniques. Anarcha faced 30 ‘surgeries’ over four years before history was finally made in 1849 (following them, opium was given to ease the pain). Nathan Bozeman, one of Sims’s assistants, later stated that only half of the ‘surgeries’ were a success.

From visualizing the vagina and cervix, gaining access to treat common uterine issues, catching cancer before it becomes acute, and diagnosing cervicitis (a prominent sexually transmitted infection); all are possible because of the speculum. Due to its effectiveness, the instrument itself has changed little in 170 years.

“[It] defines the specialty, enabling everything gynecological and obstetrical short of removing the ovaries,” Dr. Dustyn Williams, OnlineMedEd’s co-founder and lead educator says.

“Until ultrasound became prevalent over the last 20 years, using the speculum was the primary way a gynecologist could inspect female reproductive organs.”

It’s unknown what came next for his three patients. Emancipation wouldn’t arrive until 16 years after the first successful fistula ‘surgery.’

The Ear of the Last Empress

Sims’ newly found profile lured him to New York City in 1853, where he established one of the first women’s hospitals in the United States. Often practicing on poor Irish immigrants, his questionable ethic approach continued.

In 1861, he traveled to Europe where he served an extended medical sabbatical during the entirety of the Civil War. A chance to swap knowledge, teach new procedures, and enjoy foreign celebrity, European travel was common for American physicians at the time.

Though officially a neutral American abroad, the father of modern gynecology was a confirmed pro-slavery Confederate. The most famed moment of Sims’ European travels came on May 5, 1864, when he performed a successful fistula surgery on Princess Eugenie of France.

The surgery occurred days after an important Confederate victory in Chancellorsville, Virginia; arguably the high water moment for their military efforts. Bozeman, his former assistant, served as chief staff surgeon to General Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, who died in the battle.

All three events captured newspaper headlines across the continent and Sims became a confidante of the Empress. A month after the operation, a Confederate diplomat was summoned to Paris by Napoleon III to speak of the French recognizing an independent South.

It was one of the closest moments that the Confederacy got to international recognition and support.

Sims resumed private practice upon returning to the U.S, surviving a New York Academy of Medicine ethics trial in 1870, before dying in 1883. One of his grandsons would later become a famous architect, while another—John Allen Wyeth—was an acclaimed WWI poet.

Though rumors about Sims use of human beings “as experimental animals” persisted in his final years, they didn’t stop the statue from being raised in 1894.

Almost all the money for his statue was donated by fellow male surgeons. Despite his crucial role in the advancement of women’s health, no women served on the Sims Memorial Fund Committee.

No marked graves

Less than a year before he was pulled down, protestors gathered around the Sims statue demanding its removal. Their pleas came downstream of earlier acknowledgments of the true story behind Sims.

In 2006, the University of Alabama at Birmingham took down a painting depicting Sims as one of the state’s ‘medical giants.’

After the initial protest but before the statue came down, the University of South Carolina ‘quietly renamed’ an endowed chair position still in his name. A statue on the grounds of the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery remains up.

Before New York’s Mayor Bill de Blasio decided to pull the Sims statue down, a protester spray-painted ‘RACIST’ in red paint across Sims’s back and marked his eyes the same color. “[Doctor] Sims is not our hero, and we don’t need any reminders of his barbarities,” Marina Ortiz, a prominent Harlem neighborhood leader, told the Guardian.

Dr. Sims, ‘the father of gynecology’, was the first doctor to perform a successful technique for the cure of vesicovaginal fistula, yet despite his accolades, in his quest for fame and recognition, he manipulated the social institution of slavery to perform human experimentations, which by any standard is unacceptable.

“In an age defined by changing values and an evolving notion of what constitutes a fact, the Sims statue [stood] as a monument to truth’s susceptibility to lies and political indifference,” Hallman wrote, three years before its removal. “Removing it represents an awareness that history is fluid, but bronze is not.”

Critics and defenders have both scored points in the continuing fight on Sims’ story and the uncomfortable query it poses. Critics have labeled him as a heartless, racist monster driven by fame, but overplayed the availability and risk of using anesthetic. Defenders excuse his moral and ethical failings to the time they occurred and point to the countless women whose lives have been improved as reasons for his forgiveness. Hallman says both sides have succeeded in blurring the lines. “Sims’s biography [has] become a kind of post-truth zone,” he wrote.

History shows Sims to be an ambitious young doctor who worked at a time—and in a place—where a range of unethical, immoral practices removed barriers that led to ground-breaking medical discoveries; discoveries that could have sooner happened if female doctors were allowed to train at the time, anyway.

Making a mockery of the moniker that history has given him, Sims continually displayed little human regard for Black or female patients.

Dr. Durrenda Ojanuga, from the University of Alabama, wrote the best summation of the state’s famous physician for the Journal of Medical Ethics, in 1993. Though he acknowledging the importance of Sims’s discoveries, Ojanuga concluded that his manipulation of enslaved people was wholly “unacceptable.” “ … his fame and fortune were a result of unethical experimentation on powerless Black women,” he wrote.

“Dr. Sims, ‘the father of gynecology, was the first doctor to perform a successful technique for the cure of vesicovaginal fistula, yet despite his accolades, in his quest for fame and recognition, he manipulated the social institution of slavery to perform human experimentations, which by any standard is unacceptable.”

The statue of Sims is planned to be raised again in New York’s Green-Wood cemetery near the location of his actual grave. The city is facing resistance from the Brooklyn community it is located in. Anaracha, Lucy, and Betsey have no marked graves.

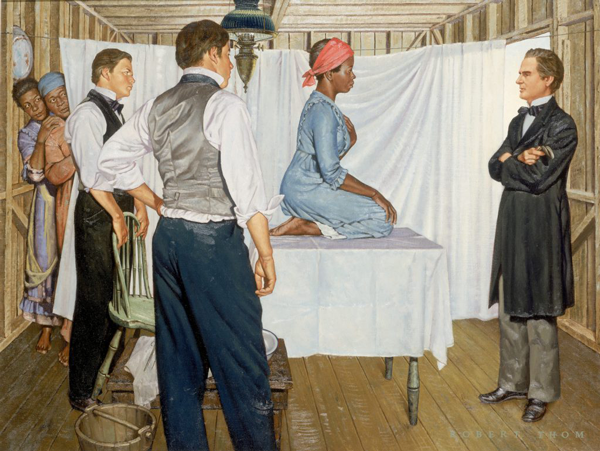

Editor’s note: The story behind the title image

As reported in the research of author J.C. Hallman, pharmaceutical giant Parke-Davis commissioned Michigan artist Robert Thom to create a series showing the history of medicine.

Completed in 1952, his oil painting of Sims showed Dr. J. Marion Sims holding his history-making speculum in a makeshift Alabama surgery. He is flanked by two assistants and “three worried slave women who would serve as his initial subjects.”

Parke-Davis, who owned the rights to the image, was sold to Warner-Lambert, a bigger fish in the pharma sea, in 1970. Thirty years later, Warner-Lambert was sold to Pfizer, producers of one of the leading Covid-19 vaccines.

Though Warner-Lambert had allowed its publication in a late 1990s history of the early years of American gynecology, Pfizer refused to grant publication rights to author Harriet Washington in 2007. Washington wished to use the image on the cover of Medical Apartheid, her groundbreaking history of medical experimentation on Black Americans.

After reviewing the manuscript, Pfizer declined making the image available. A further request for a smaller image inside the book wasn’t responded to. Thom’s painting of Sims is now kept in the collection of Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, which made it available for use on The Rotation. – Ben Stanley